It’s not always on their minds. But there are moments when it rushes to the forefront. Lizette was at school working on homework when a boy in her class jokingly said he’d call immigration on her and her family. Maria was excitedly talking to her father about the internship program at her new high school, when he told her to be careful, because they would probably ask for a Social Security number when she applied.

Lizette and Maria are both 16-year-old juniors in Oakland high schools. They’re dedicated students and are active in the youth group at their church. They are also undocumented.

Neither Lizette nor Maria, whom the Express has agreed not to identify because of their immigration status, were allowed to enroll in the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals program. DACA provides protections to young undocumented people who came to the United States as minors. If President Trump and Congressional Democrats and Republicans reach a deal to protect young, so-called Dreamers, Lizette and Maria could become eligible for protections.

Maria’s family landed in the United States on June 17, 2007 — just two days after the cut-off date for DACA eligibility. Lizette didn’t apply for DACA when the Obama administration first rolled out the program in 2012. But when she turned 16 last January, she wanted to work, so her mother suggested she apply. In August, she filed an application, but then a month later, her family’s lawyer called with bad news: No new applications would be accepted. Following the Trump administration’s September decision to “phase out” the program, Lizette and Maria’s hopes for an immediate path to any sort of legal immigration status have dimmed.

On a recent weeknight, before a youth group meeting at their church, Maria and Lizette joked and talked about school and the church band. Maria plays electric guitar and Lizette plays keyboards.

“Part of me felt bad, really, really bad,” Lizette said as she fingered the corner of her jean jacket. “I try to be positive, you know, like this is not stopping me. But it’s hard, honestly. It’s really hard, because I missed out on so much — scholarships, programs — so much.” Maria, sitting next to her in the classroom above the sanctuary where their youth group meets, nodded, tucking her long dark hair behind her ears.

“Also, for me, it’s like thinking after I’m at junior year, thinking when I turn 18 …” Maria trailed off.

“Like, whoa, what am I gonna do after that?” Lizette finished her sentence.

Maria’s voice suddenly broke, and tears came to her eyes. “Like how’s it gonna be — my life? It’s something I think about more now. Like, you feel normal but…”

“You feel different,” Lizette said softly.

On Jan. 9, federal judge William Alsup in San Francisco blocked the Trump administration’s plan to shut down DACA. Under the judge’s order, those whose DACA protections expired on or after Sept. 5, 2016 will be able to renew their status for an as-yet-undetermined period of time. However, Alsup did not require the federal government to accept new applications. Late last week, the Trump administration appealed Alsup’s ruling.

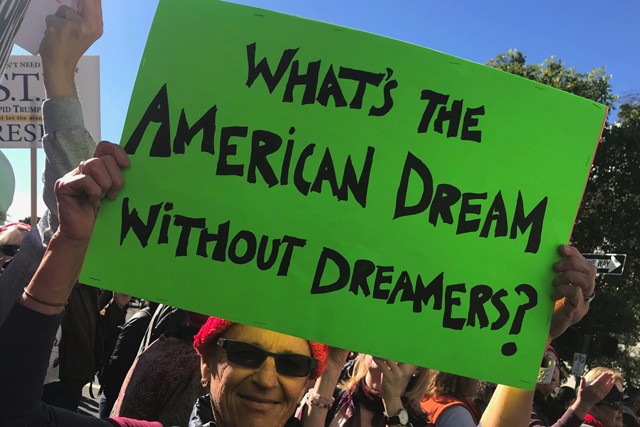

The most recent version of the Development, Relief and Education for Alien Minors Act, or DREAM Act, is at a stand-still in Congress, and the dispute over it has shut down the federal government on Saturday and Sunday. But the Dream Act represents the best chance for Lizette and Maria and those like them who never qualified for DACA to pursue an open life in the United States.

DACA provided protections for nearly 700,000 people when Trump announced that he was ending it. The current version of the Dream Act, which aims to give young people a pathway to citizenship, would likely expand the number of undocumented young people protected to close to 2 million. It would also help the economy. The Center for American Progress, a liberal Washington, D.C. think tank, estimates that the present number of DACA recipients would contribute more than $460 billion to the nation’s GDP over the next 10 years.

“You live life normal,” Maria said of being an undocumented youth. “It’s not like I think about it 24/7, like I’m an immigrant. No. You live your life normal and it’s just when you want to do something…”

Maria got up to get tissues. When she returned, Lizette reached over and rested her hand briefly on her shoulder.

Lizette picked up the conversation. “My school is a college-based school, so everything is related to college and I feel like when we have college seminars and stuff like that, it kinda hurts,” she said. “It’s like Pell Grants, Cal Grants, and it’s like, ‘Oh, half of the people there don’t qualify and the other half qualify.’ It kind of hurts when you’re really trying your best and there’s still this one line, and it’s a boundary and you can’t pass it.”

They talk about their fears about being forced to go back to countries they don’t know and how even within their own communities there’s discrimination toward people without legal immigration status. Lizette said that “if this weren’t an issue,” she’d go to a four-year college and become a teacher, and eventually a principal. Maria talked about how spending the summer painting houses with her dad got her interested in real estate.

There was about 20 minutes before youth group was to start. Inevitably, the conversation turned back to school and homework — the everyday grind of teenagers. Maria talked about her music production internship; she loves that electronic music is like making “something from nothing.” She recently learned how few women are in music production, effortlessly sliding into a discussion about how women are seen as performers, entertainment rather than producers. The two friends spoke about everything from homelessness to climate change to Howard Zinn’s A People’s History of the United States. They talked about how their parents inspire them and how they both tell their mothers everything.

When they joke, they laugh without restraint, free for a moment from stresses the average American teenager has no concept of.

Lizette began a conversation about free will, the main theme of Kurt Vonnegut’s Slaughterhouse-Five, which she’s reading for her Advanced Placement English class. She said that despite how confusing it is, it’s now one of her favorite books. Fate and free will are in conflict in her and Maria’s lives right now. They cope in their own ways.

Maria deals with it by being an activist, knocking on doors for Oakland Community Organizations, a progressive coalition of schools, congregations, and local agencies. “I don’t like to think about it,” Maria said of her immigration status. “I’m gonna live my life normally. Nothing’s gonna stop me. I’m not doing anything wrong. I’m just trying to live a life.”

Lizette takes a slightly different approach. She buries herself in her schoolwork, constantly challenging herself to do better. (She kicks herself over her current B in AP English — she’s used to straight As). “We’re kind of like bugs in an amber,” she said, paraphrasing a Vonnegut quote. The imagery is apt — Lizette and Maria both often refer to a feeling of being stuck, suspended by forces beyond their control. For this reason, Lizette relates to Billy Pilgrim, the protagonist of Slaughterhouse-Five. “We have to live our lives and not just think about the bad stuff,” she continued, explaining the quote from the book. “All I can do is wait, hope for the best, expect the worst.”