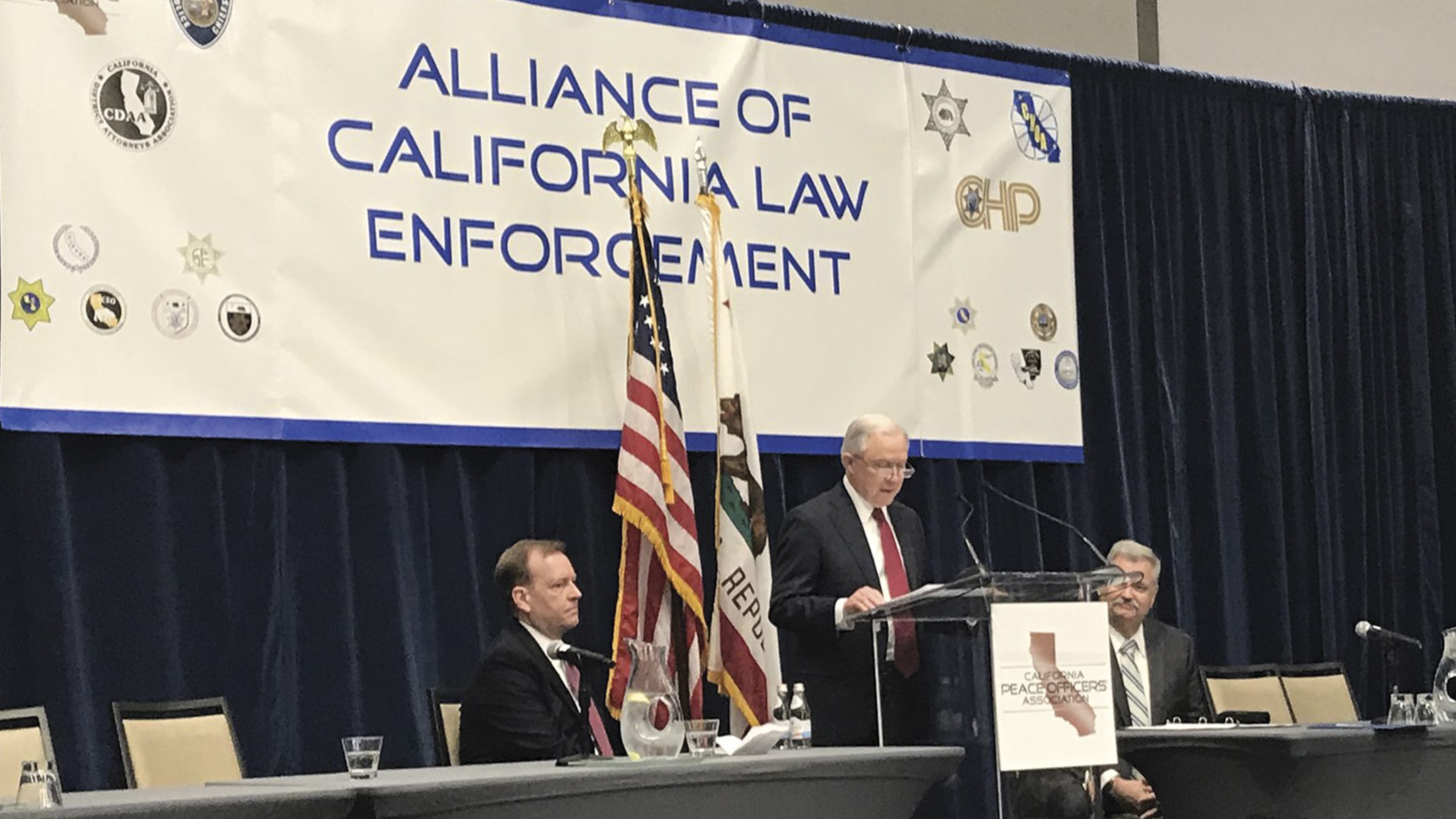

In a speech before a law enforcement lobbying group in Sacramento earlier this month, U.S. Attorney General Jeff Sessions attacked California political leaders, calling them “lawless open borders radicals,” and announced a lawsuit to overturn the state’s sanctuary laws. In response, dozens of state lawmakers held a protest and pledged to step up their resistance to the Trump administration, while Gov. Jerry Brown derided Sessions’ visit and called his lawsuit a “political stunt.”

Sessions’ trip marked a deepening rift between California and the federal government. It also further exposed a different divide: one inside the state that is widening and having far more influence on immigration and criminal justice policy than anything the Trump administration is doing.

In recent years, California’s police and sheriffs’ departments and district attorneys have played their own role of resistance — against a wave of progressive criminal justice and immigration reforms that state voters and political leaders have embraced. Through their rank-and-file unions and statewide lobbying groups, cops and prosecutors have fought nearly every progressive criminal justice proposal and the same California pro-immigration policies that the Trump administration hopes to topple. And they’ve strongly backed right-wing firebrands like Sessions.

“Law enforcement tends to unify against criminal justice reform, both in the legislature and at the ballot box,” said Ana Zamora, criminal justice policy director of the ACLU of Northern California.

“If you look at what California voters and lawmakers passed in terms of Proposition 47 and SB 54, the mainstream has moved away from dumb-on-crime policies,” said Zachary Norris, executive director of the Ella Baker Center, referring to the criminal justice reform ballot measure approved by voters in 2014 and the state’s new sanctuary law, respectively. “But these law enforcement associations are out of step.”

They might be out of step with the state’s liberal majority, but police and prosecutors continue to wield significant political power. And their views are more aligned with the conservative law-and-order positions espoused by the Trump administration than with California residents and elected leadership.

Sessions, for example, was hosted in Sacramento by the California Peace Officers Association, one of the state’s more powerful police lobbying groups, despite pleas from state lawmakers not to give him a bully pulpit. Assemblymember Eloise Reyes, D-San Bernardino, for example, told CPOA President Marc Coopwood, who is also a Beverly Hills’ assistant police chief, in a letter, that by hosting Sessions, the group provided him with a “platform to espouse his anti-immigrant and harmful rhetoric.” State Assembly Speaker Anthony Rendon, D-Los Angeles, tweeted a copy of Reyes’ letter, adding, “@CalPeaceOfficer should revoke its invitation to have Mr. Sessions speak in Sacramento tomorrow.”

CPOA didn’t revoke, and Sessions earned applause from the group’s members when he credited former President and California Gov. Ronald Reagan and Reagan’s attorney general and Drug War proponent, Edwin Meese, with a multi-decade drop in violent crime in the state. Sessions then expressed disdain with California’s recent progressive turn. “Maybe, in recent years, we got complacent and took our eye off the ball, but recent trends are deeply worrisome,” he said. (California’s violent crime rate rose slightly in 2016 — by 3.7 percent — although its overall crime rate is at historically low levels.)

Last week, the CPOA’s immediate past president and current board member, Sacramento County Sheriff Scott Jones, attended a White House immigration roundtable where he told Trump that California’s sanctuary policies are a “spectacular failure” and described how he’s embedded ICE agents in his jail.

California law enforcement’s backing of Sessions preceded his ascent to attorney general. Last year, when he was first nominated by Trump, the Peace Officers Research Association of California (PORAC), which has 69,000 law enforcement members, sent a letter of support to the U.S. Senate urging Session’s confirmation.

But it’s in Sacramento, not Washington D.C., where the state’s law enforcement groups are most influential.

According to Angela Chan, a civil rights attorney with the Asian Law Caucus, law enforcement groups routinely block or delay reforms through the sheer number of lobbyists they employ. For example, in 2011, Chan was at an Assembly committee hearing to support AB 1081, an early version of the Trust Act, which was intended to stop sheriffs’ offices from participating in the federal Secure Communities Program. Under Secure Communities, the fingerprints of everyone booked into local jails were automatically sent to immigration agents. If the prints identified an undocumented immigrant, ICE could then send a “detainer request” to the sheriff asking the jail to hold the person so deportation agents could take him or her into custody.

All of California’s sheriffs participated in the program. The Alameda County Sheriff’s Office was an early adopter, holding upwards of 155 immigrants daily on ICE detainers, according to a 2010 San Francisco Chronicle report. But many of those deported under Secure Communities hadn’t been convicted of a crime. Others were only facing nonviolent, misdemeanor charges. Multiple federal judges subsequently ruled that detainers are unconstitutional because they extend the jailing of individuals for whom local sheriffs and police have no legal cause to hold them.

Even so, passing the Trust Act took years due to resistance from the California State Sheriffs’ Association.

Alameda County Sheriff Gregory Ahern was a prominent opponent of early versions of the bill, as were the sheriffs of Los Angeles and Orange counties. Also on the sheriffs’ side was the anti-immigration group Californians for Population Stabilization — which has blamed immigrants for violent crime and even the state’s drought.

“We were in the committee hearing room, and we were surrounded by law enforcement lobbyists,” said Chan about the 2011 hearing. “They’re in Sacramento day-in, day-out. They don’t have to make a special trip. They’re there all day long, lobbying.”

AB 1081 died in 2012 when Gov. Brown, adopting the sheriffs’ position, refused to sign it because it limited their ability to cooperate with ICE. “Los Angeles Sheriff Lee Baca really went after the Trust Act in 2012 and helped one version of it get vetoed,” said Jon Rodney of the California Immigrant Policy Center. “He threatened he wouldn’t follow it.”

An amended version giving sheriffs more latitude to work with ICE was introduced in 2012 but they remained opposed and were joined by the California District Attorneys Association and PORAC. But by then, public opinion had shifted further in favor of protecting immigrants, and Gov. Brown signed the Trust Act in 2013. “It took three years to pass it,” said Chan.

Still, in subsequent trips to Sacramento, the first question she’s asked by state lawmakers about immigration and criminal justice legislation is whether law enforcement groups support or oppose the bill, she said.

In addition to employing numerous lobbyists in the capital, law enforcement groups are a major source of campaign funds for politicians. PORAC, as just one example, contributed more than $12 million to the campaigns of 272 candidates for state office over the past 17 years.

Norris ran up against the power of law enforcement lobbyists in 2008 when a coalition of police unions and wealthy conservatives put Proposition 6 on the ballot. If passed, Prop. 6 would have set aside nearly $1 billion in additional state funds for jail expansion, prohibited undocumented immigrants from being released on bail or their own recognizance if charged with a violent crime, and allowed prosecution of juveniles as young as 14 years old as adults.

PORAC and the Richmond Police Officers’ Association were major financial supporters of the measure. Alameda County Sheriff Ahern’s campaign committee also contributed funds. In total, law enforcement groups spent $1.9 million promoting it. Opponents spent $2.6 million and defeated the proposition.

“It was defeated with 70 percent of the vote,” said Norris, who called the win a “watershed” moment that showed progressives could beat police and sheriffs at the ballot box. Since then, voters have passed four major criminal justice reform propositions.

Proposition 36, which received 70 percent of the vote, undid parts of California’s three-strikes law, which was responsible for a massive increase in the state’s prison population. According to a report prepared by the ACLU of Northern California, 55 of the state’s 58 district attorneys opposed Prop. 36. While Alameda County DA Nancy O’Malley remained officially neutral, Contra Costa County’s then-DA Mark Peterson was an outspoken opponent, despite 72 percent of voters in his county supporting the change.

Zamora said it’s a pattern: DAs and police almost always oppose reforms that a majority of voters in their counties want. Unions representing deputy DAs, cops, sheriffs, prison guards, and probation and parole officers finance ads calling the reforms dangerous. In the 1980s and 1990s, their united front was able to pass numerous tough-on-crime laws.

But by 2014, 60 percent of voters approved Prop. 47, which shortened sentences for people convicted of nonviolent property and drug crimes and reduced some nonviolent crimes from felonies to misdemeanors. The measure was designed to reduce the prison population and better fund reentry services. In an op-ed, O’Malley called Prop. 47 a “frightening fraud” and “Trojan horse,” and the California District Attorneys Association, of which O’Malley is currently the second vice-president, funded the “No On 47” campaign.

The California State Sheriffs Association, which also opposed Prop. 47, is, by many measures, the state’s most conservative large law enforcement organization — and the oldest. Founded in 1894, the sheriffs’ association helped professionalize and modernize aspects of policing, such as adopting a uniform system of identification using fingerprints. But in the early 20th century, the group also saw its purpose as “the prevention and curtailment of communistic disorders” among agricultural workers and preventing the migration of “hobos” into the state, according to press accounts at the time.

The sheriffs’ association continues to take a hard line on immigration. For example, on its candidate questionnaire, which the group uses to determine who it will endorse, it asks whether they will “support increased funding for the Border Patrol and other actions to secure our borders.”

Sheriffs’ association Legislative Director Corey Salzillo said that while sheriffs don’t patrol the border or enforce immigration laws, they are concerned about transnational crimes like drug smuggling and human trafficking and want to support federal agencies focused on border issues.

Like PORAC, the state sheriffs also supported Sessions’ nomination to become U.S. attorney general and sent a letter to the U.S. Senate urging his confirmation — signed by Ahern and Kern County Sheriff Donny Youngblood. A group of six California sheriffs, including Contra Costa County Sheriff David Livingston, also visited Sessions in Washington last year to convey their support for him.

The sheriffs were by far the most vocal critics of the statewide sanctuary law, SB 54, approved last year. Salzillo said the biggest issue of concern for the sheriffs was simply the limitation on their ability to communicate with ICE about undocumented immigrants held in their jails, and the limited number of crimes for which an inmate could be reported to ICE.

“In the end, there was a whole slew of amendments, lots of carve-outs,” said Chan about the final version of SB 54. Among other things, the sheriffs’ association, California Police Chiefs Association, and other groups got the law amended to allow cops to participate in ICE task forces, so long as the main focus is not immigration enforcement.

East Bay Assemblymember Rob Bonta, D-Alameda, said the invitation Sessions received to speak to the CPOA, and to attack SB 54 and other state priorities “wasn’t the best moment for the law enforcement community.” Still, Bonta said he doesn’t think California’s cops are swimming against the tide of popular opinion because they’re aligned with Trump and Sessions’ views on immigration and crime. “I don’t think that’s the view law enforcement takes,” said Bonta. “I didn’t get the sense that this was their guy, and this was their rallying cry.”

Ella Baker Center’s Norris holds a different view. “Right now, you have public health advocates, unions — not law enforcement associations, but actual unions — and other groups pushing reform policies. But law enforcement groups, they’re out of step, and they’re being rallied by someone who is clearly out of step.”