Since he was thirteen years old, Michael Schiess has been obsessed with pinball machines. He has driven across the country to collect them. A year and a half after starting his Pacific Pinball Museum in Alameda, he has never taken home a salary higher than $1,600 a month, so he and his wife make ends meet by renting out the bottom half of their house. When doctors recently informed him that his arthritic hip may need to be replaced — meaning he could never lift a pinball machine again — the 56-year-old electric mechanic responded, “No, thanks. See you later!”

As a result of his dogged perseverance, Schiess now manages the largest collection of rare pinball machines in the world. There are seven decades’ worth of playable pinball machines in his 4,000-square-foot museum, the first to publicly curate the games as artifacts of American art, science, and pop culture. But he believes that the preservation of the collection depends on the museum expanding into a bigger and more permanent space.

Michael Schiess wants to expand his Pacific Pinball Museum, but so far he can’t find a home for it. Credits: Stephen Loewinsohn

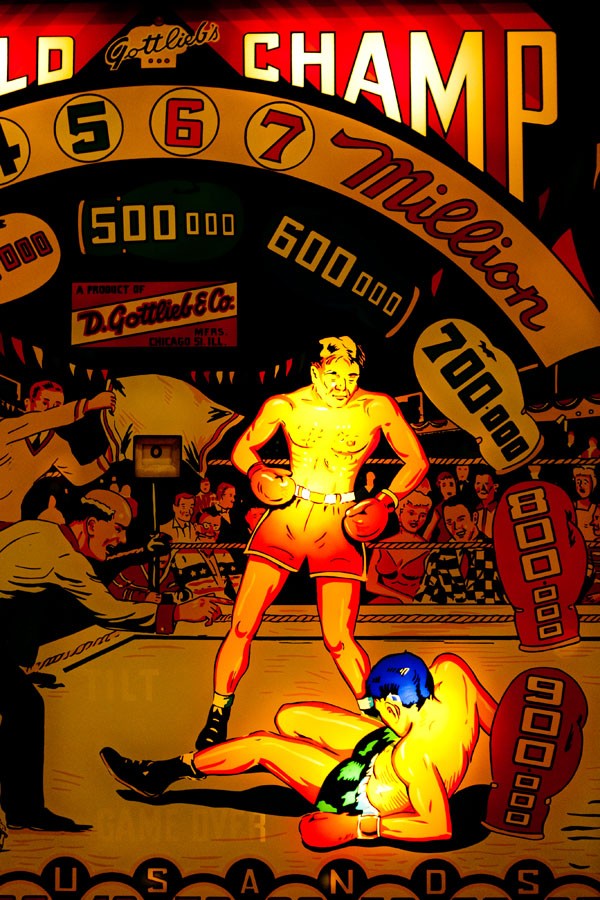

Pinball art, such as this back glass, reflected the times. Credits: Stephen Loewinsohn

Pinball Mac still holds private pinball parties in his basement in Berkeley, but he thinks the game’s money-making days are over. Credits: Stephen Loewinsohn

The Pacific Pinball Museum relies on volunteers like Christopher Nash, aka “The Pinball Doctor,” who travels to Alameda twice a year from his home in Portland, Oregon, to help repair and restore the museum’s collection. Credits: Stephen Loewinsohn

Seven hundred pinball machines are stored in a warehouse in Alameda because the museum doesn’t have room to display them. Credits: Stephen Loewinsohn

Specifically, Schiess has his eye on creating a 40,000- to 50,000-square-foot “Smithsonian of pinball museums” in a long-vacant warehouse on Alameda Point. He pictures it becoming a recreational destination that draws people to the city the way Neptune Beach, the legendary beachfront amusement park, did in the early-1900s. The problem is, the City of Alameda doesn’t seem to give a damn. So far, city officials have not responded to Schiess’ requests for support, or even to his invitations to visit the museum.

“For how many people we bring into the city, it’s amazing how much they ignore us,” Schiess said. “I thought when we asked about this old, vandalized space they were going to say, ‘Sure, fix it up. What else are we going to do with it?’ But before they’d even let me see the inside, they wanted me to draw up plans and see how much money they could get out of us.”

Schiess’ museum not only preserves an endangered piece of American history, but it could also be a huge boon to the island city, and to the East Bay. Despite the fact that video games have almost completely decimated the pinball industry, and that only one company in the world, Chicago-based Stern Pinball, still makes pinball machines, Schiess believes we’re in the midst of a full-blown pinball renaissance. And, indeed, he appears to be right.

Pinball tournaments have grown so popular at the Pacific Pinball Museum that Schiess stopped advertising for them. On one day in December, more than 4,000 people bought admission tickets through Groupon. Increasing numbers of youth groups visit the museum for field trips, and he’s booking more and more pinball parties. A showcase at the San Francisco International Airport featured the museum’s pinball games as art, while companies such as Google and Genentech have rented part of the museum’s collection for company events. The annual Pacific Pinball Expo Schiess helped start and organize for the last four years in San Rafael now draws thousands of visitors from more than twenty countries, and is the largest pinball expo in the world. And if imitation is a form of flattery, the Pacific Pinball Museum is getting plenty of it from pinball museums now popping up all over the country — even in Australia.

But Schiess’ machines — which are restored and repaired entirely by a crew of volunteers — may be threatened if he doesn’t find a new home for them, and soon. The lease on the warehouse where he stores them is up for renewal in a few months, and he’s growing increasingly uncertain as to whether his collection can continue to be stored there. Protecting the games from the water that seeps through the leaky roof is of utmost urgency. Trickling water currently threatens the rarest flipper-era machine, Mermaid, an illustrious 1951 David Gottlieb masterpiece valued at $17,000.

“We’ve got a lot of important American culture here,” Schiess said while working in his warehouse one evening. “And we want to be in a facility that should be totally clean and environmentally controlled. But we’re in a warehouse because this is what we can afford. We don’t get any funding and grants — this is just a lot of people throwing their backs into this thing and making it work.”

So far, he’s been unable to afford a large space anywhere else. There is a small chance that the pinball museum could move next to the Exploratorium when it eventually relocates to San Francisco’s Embarcadero waterfront. But in the meantime, Schiess just hopes that he and his volunteer team can keep the ball rolling in the East Bay.

For how much longer, however, is unclear.

This gambling mania is even worse than liquor as a spectacle of complete waste. It’s a waste of money, a waste of time and social waste. The very atmosphere of respectability associated with slot machine clubs adds to the sum total of evil.” — Daniel A. Poling, national church leader speaking out against pinball clubs in the Spokane Daily Chronicle, 1949

Schiess was thirteen and living in Albuquerque, New Mexico, when he got hold of his first pinball machine. His father was an engineer and a tinkerer with a backyard scrap heap. When a nearby car wash closed, Schiess rolled a wheelbarrow down to the abandoned site just to see what interesting junk he could find. “One of the things I found was this big arrow with all these big bulbs on it that would light up,” Schiess recalled. “I got it going again and traded it to my friend for a pinball machine. I’m pretty sure it was a Gottlieb Kings and Queens. We beat the crap out of it.”

From the moment he laid eyes on the game, Schiess was endlessly fascinated at how alluring a simple game could be. Some mystery about human desire had to be lurking inside it.

“I always thought that, as a species, that it was pretty amazing we came up with this amusement box,” Schiess said. “That always blew me away. You just put a quarter in and this ball starts bouncing around? That’s it? So then I did it, and thought, ‘Wow. This is fun. So this is what humanity has been bred for.'”

What he didn’t know then was that he was joining a long line of Americans who had been just as fascinated by the simple goal of keeping a ball bouncing around a playfield. According to pinball historians, that line started during the American Revolution. French soldiers brought the bagatelle, a pinball precursor, to the New England colonies along with the martial power needed to defeat British rule. Players shot balls with cue sticks around a small box with nails, or pins, used to ricochet them into holes with varying point values. Apparently, it was French King Louis XIV’s favorite game. Bagatelle continued to be played in America by the poor and the presidential for more than a century. Schiess has one from 1879, displayed under glass at the front of his museum.

Then Baffle Ball, one of the first coin-operated pinball games, hit the American market in 1931 with such force that its producer, David Gottlieb, couldn’t manufacture enough to meet public demand. The wooden tabletop game featured baseball-field bases and bagatelle-like pins nailed into the playfield. The game didn’t have flippers yet; scoring depended entirely on the force with which you plunged the ball into the game. One cent bought a player seven balls, which made Baffle Ball an overnight hit for a Depression-era public eager for cheap entertainment. Enough points won the player either free games that they could sell to others or a coin payout.

Within a year of Baffle Ball‘s release, at least 150 other pinball manufacturers had popped up, all started by individuals tinkering in their garages. Some were even funded by National Recovery Act grants. A restored Baffle Ball game is displayed at the museum, but it is still off-limits to everyone but Schiess and other museum personnel, who love to show people how it works. “You got to kind of knock it around to make anything go right,” Schiess demonstrated. The devices became even more exciting with the 1933 Rockola World Series: The plunger that sprung the ball into play wound up a set of rotating infield bases that could be filled with multiple pinballs and “hit” home.

Proliferating styles of the game proved addictive for so many people that pinball was illegal for decades in many US cities, including New York, Chicago, Los Angeles, and Oakland. Because of the coin slots they shared with slot machines of the day, pinball games were associated with gambling rings that financed now legendary New York City criminals: Frank Costello, Charles “Lucky” Luciano (often considered the father of modern organized crime in America), Benjamin “Bugsy” Siegel, Jacob “Gurrah” Shapiro, and Louis “Lepke” Buchalter (the latter two created Murder, Inc., a nationwide murder-for-hire syndicate).

In the weeks following the attack on Pearl Harbor, New York Mayor Fiorello LaGuardia told police their top priority would be confiscating pinball games, then smashing each in public with sledgehammers. (Photos of these bashing sessions grace one of the walls of the Pacific Pinball Museum.) At first, the crushed remains were sunk like murdered bodies into the Hudson River. But once scrap drives started for World War II, newly confiscated pinball games were instead turned into 7,000 pounds of scrap material, 3,000 pounds of it from steel balls. There’s a good chance, in fact, that pinballs once fired at imaginary enemies were melted down into bullets that were fired at very real ones.

On the opposite coast, similar pinball raids were taking place in Oakland. A Bally Bumper from that era, the first game with electronic bumpers and scoreboard, was saved from destruction in Oakland by a policeman who hid it in his garage in Alameda. The cop played it and kept its minimalist art deco designs in mint condition for seventy years; when he died, his brother donated it to the Pacific Pinball Museum. Games like Bally Bumper didn’t have flippers yet, either; as Schiess demonstrates, the large antique box has to be physically tilted and knocked to score points. (That’s why “tilt” sensors were later added to pinball machines).

To survive the illegalization movement and conserve materials during World War II, pinball manufacturers started focusing more on interchangeable art than on building new games. Colors multiplied and were lit more brightly. Bells rang louder. Imagery became sexier and more carnivalesque. One of the most popular was Gottlieb’s 1954 Dragonette. The Roy Parker back-glass art of a scantily clad woman is a soft-porn parody of the TV crime drama Dragnet. While a suspect in the corner glances at her and grabs a pickle from a barrel, a detective says to her, “Just want the facts, mam! The bare facts … mam.” By the Fifties and Sixties, rebellious youth inching toward an era of sexual liberation were emptying their pockets for pinball in such numbers that the game made more money than the entire film industry.

In the late-Sixties and early-Seventies, pinball fever was the center of the first rock opera, The Who‘s Tommy. The story centered on a traumatized kid who goes from being exploited for his disabilities to being religiously worshipped as a pinball champion. That deaf, dumb, and blind kid, as the classic rock hit “Pinball Wizard goes, sure plays a mean pinball.

But that proved to be the height of cultural consciousness of pinball. With the advent of video arcade games, pinball’s popularity faded; by the mid-Nineties, home video games had taken over, and the only pinball machines left in public were lonely, corner wallflowers in the dwindling number of bars, restaurants, and bowling alleys willing to maintain them.

But that didn’t mean that guys like Schiess didn’t love the game anymore.

“Once you eject that ball, chaos theory comes into play. No two games of pinball are the same,” Schiess said. “It’s not like a video game where every possible outcome is programmed into it.”

While pinball’s cultural significance waned, Schiess decided he’d finally do more than play the game; he’d take a deeper look at what exactly went into a pinball machine — by designing his own. It would be a sacrilegious machine called “The Last Supper,” featuring Jesus Christ, his disciples, and ladyfriends getting their divine drink on. He wanted to design it in the style of one of his favorite pinball back-glass artists, Christian Marche, who drew uber-mod characters with sharp angles and gracefully elongated limbs.

But as he reconstructed the old pinball body he wanted to use for it, Schiess fell in love with the creative electromechanical and geometric designs used to make the machine work. And that led him to learning how entire teams of artists, engineers, and game theorists spent weeks, even months designing the strategy and creating the story behind each game.

Schiess wanted to find more vintage pinball machines to play, but they were hard to come by. He couldn’t afford to fully indulge the endless appetite he now had for vintage machines, so he started putting feelers out for other pinheads who might invite him to play their collections. He had heard of one guy, a legend of the Bay Area’s pinball subculture, who for the past decade held a secret pinball party in a basement marked only by a glowing blue-violet light bulb.

Suddenly, Schiess decided, finishing “The Last Supper” was much less important than finding this guy.

Starting in 2000, Schiess spent his Thursday nights cruising residential neighborhoods in the East Bay looking for that light bulb. Where the hell was it? He knew he had to acquaint himself with this local pinball kingpin, who sounded like one of the few pinheads who had truly fallen in love with the game’s art and construction as much as Schiess had. But for two years, Schiess’ search proved fruitless.

“It was so secretive, I didn’t even know what city he lived in,” Schiess recalled. Then, while shopping for house wares in a downtown Berkeley store one day, Schiess began chatting with a tall, free-spirited guy who worked there. The conversation hovered around Schiess’ vintage motorcycle until he spotted something in the back of the shop.

“Is that … a pinball machine?” Schiess asked.

“Yeah, I fix them up on the side,” the guy said. “You got one?”

“Yeah.”

“Oh, well, you should come to this thing I do at my house on Friday nights.”

“You’re — you’re that guy?”

Schiess had found his man. He went by the name Pinball Mac. That Friday night, as he made his way toward the blue-violet light bulb that illuminated an inconspicuous basement door in Berkeley, Schiess had no idea this would be a turning point in his life.

On the other side of the door, within a room whose walls and ceiling were covered with kitschy holiday ornament lights, toys, comics, and masks of US presidents, was a kaleidoscopic wonderland of pinball machines. Lights glowed and seductively danced around the back-glass art and playfields of more than forty vintage games, each one set on free play for Pinball Mac’s most dedicated pinheads and their friends. No other place in the country had such an operating collection. “It was mind-boggling,” Schiess remembered.

Games from almost every decade, stretching back to the 1930s, represented the fantasies of each era. On “Ship Mates,” imaginary swim-suited babes swarmed a hard-up sailor. Other games took the player to a circus, a burlesque show, or into outer space. Year after year, decade after the decade, the games transformed and increased in complexity in order to entice and entrance a new generation of players. Despite the ubiquity these American-made machines enjoyed for so long, all over the world, the games are now exceptionally rare — playable versions even more so. Only a small number of machines found their way into the hands of aficionados who could repair and restore them.

Pinball Mac wasn’t the classic “gamer” type interested in beating everyone else’s high score. It was only after being pressured to use his electrical engineering skills to fix a friend’s machine that he fell in love with their history, artwork, and creative mechanisms. Pinball Mac’s lair had become a place where an underground subculture of pinball collectors and lovers could not only share a unique addiction, but network. Some of Mac’s guests owned machines as well, many of which were obtained in the early-Nineties, when Mac helped rescue about five hundred machines from a warehouse in Omaha, Nebraska, shipping them to the Bay Area on a Union Pacific train.

At Mac’s place, Schiess realized what else he loved — this atmosphere of people kicking back and reviving artifacts of American pop-culture history. But he was deeply bothered by the thought of private collections, such as the one in Mac’s basement, fading and dying along with their owners. His gut told him that if the public had a chance to see and experience pinball history, the game’s popularity could be revived. And in Mac’s basement Schiess met others, like Dan Fontes, who believed the same.

“In the Eighties and Nineties, you had this rise and fall, rise and fall, based on the success of certain games,” Fontes said. “But what’s unique about this point in time is that there’s this wave of privately owned pinball machines, pinball shows, and now a third wave of small pinball museums, and that had never happened before. There’s something about the American identity to be discovered in these games. The love of inventing, tinkering, amusing, winning, and even cheating to win are all very American.”

So six months later, Schiess respectfully asked Mac if he could start his own pinball lounge. Mac gave him not only his blessing, but also a neon “Lucky Juju” sign that had once hung outside his basement. Schiess displayed it next to the doorway of the small pinball parlor he started in 2002, and named the parlor, accordingly, the Lucky Juju.

It was the beginning of what would soon become the most ambitious collection of vintage pinball machines in the world.

As Schiess’ network expanded, collectors across the country came out of the woodwork to donate their games. One collector from Florida — who spent half his life hunting for games up and down the East Coast — has donated 240 wood-rail machines from the Fifties. Another local collector has promised his 800-plus collection, including many one-of-a-kind pieces. The rest came from a large network of Bay Area pinheads who have chosen to splurge on pinball games instead of Porsches for their mid-life crises, and who eventually realized that the whole concept of the game might die with them if they don’t find a way to cultivate another generation of enthusiasts. Some lent financial support and eventually comprised what would become the board members of the nonprofit Pacific Pinball Museum.

Ninety machines — a small fraction of Schiess’ collection (he has about seven hundred stored in his warehouse) — are on display at the museum, which is open six days a week. For $15 ($7.50 for kids under twelve), guests can play for as long as they’d like. The museum’s walls are painted with the bold, pop art imagery of vintage pinball bumpers. Light bulbs that glow like neon Broadway marquees frame images of Ginger Rogers and Fred Astaire look-a-likes on machines from the Forties; from the Fifties, there are sexy, multi-colored parodies like Dragonette; Jetson-esque artwork prevails in the space-race era of the Sixties; sex and rock ‘n’ roll rule the Seventies with games like Captain Fantastic, which features Elton John as a pinball wizard pursued by busty groupies.

Despite the museum’s success, Pinball Mac remains skeptical of Schiess’ enterprise.

“Pinball’s money-making days are over,” said Mac at one of the Friday-night meet-ups he still hosts. “They’re nowhere near as cost-efficient or convenient as video games, and we’re not going back in time. Some have more metal parts than most cars do these days. I’d rather just maintain and open up my games to others for fun.”

But for Schiess, building up the pinball museum has never been about making money, and that in itself, ironically, has helped the facility rack up enough monetary support and contributions to make it what it is today. As word got around that Schiess was building a nonprofit to revive pinball, he traveled around the state to pick up individual donations. Two years ago, Schiess travelled cross-country to do so, along with Larry Zartarian, the museum’s board chair, and Pacific Pinball Expo founder Jim Dietrick. That trip led them to the unique collection of Gordon “Gordo” Hasse.

Hasse, an ad executive, spent half his life plotting road trips from New York City to basements and warehouses in small towns from Kentucky to Maine just to pick up pinball machines. Afraid of having them commercially shipped, Hasse would pack the machines into his station wagon, sometimes daring to strap two to the roof of his car. “It was tedious,” Hasse said of the process. “But I couldn’t let any of them get away from me! There was always the chance I’d never find one of them again.” His searches, which began in the Sixties and came to a close just as eBay matured, amassed the collection of 240 Fifties-eras Gottlieb wood-rail machines that he eventually donated to the Pacific Pinball Museum. Similar to Schiess, Hasse doesn’t consider money a part of his interest in pinball. “It was just never my motivation,” he said by phone from his home in Orlando, Florida. “I collected because I value the games inherently and I want them to be available to be seen and played. The average person younger than 55 has never even seen a wood-rail.”

But Schiess also gets support from pinheads who have a more old-fashioned attitude about pinball. One is Tim Arnold, director of the Pinball Hall of Fame in Las Vegas. His place is set up more as a moneymaking arcade than a museum.

“Tim Arnold called them ‘quarter whores,’ and I thought, what is he talking about?” Schiess said. “And from an operator’s perspective, yeah, [the machines are] either pulling in the quarters or it’s ‘Get back out there and pound some pavement, bitch.’ But I just keep on looking at him and he says, ‘Mike, you’re still in the romantic stage. Soon you’ll begin to see them like we see them.’ But I don’t think I could ever leave that [stage], because if I did, it would kind of change the whole thing for me.”

For Schiess, preserving pinball is about preserving his favorite American invention.

“Pinball is a nice slice right through the heart of American culture,” he said. “It’s one of the things I think America can be really proud of because we did pinball better than anyone else and we still do. Europeans tried to build some but they just were never as popular as the American ones. We seem to get beat at our own game with cars, electronics, and other technologies. But they can’t touch us on pinball.”

Every Monday night, a rotating cast of more than twenty volunteers shows up to maintain or restore some 1,300 machines. On average, a dedicated team effort can fix up to three games a month. Some of the volunteers are just learning the ropes of repair, by learning how to wax down playfields and degrease smaller parts. Others, like Christopher Kuntz, are experts. Kuntz often comes in still wearing his work shirt from his full-time job repairing arcade games. Working on the vintage machines in Schiess’ warehouse, he said, is a privilege.

“Even in my line of work, where I’m picking up the phone every day to repair someone’s pinball machine, coming across a lot of these is very rare,” Kuntz said, while working with Schiess on the complex circuitry beneath a pinball playfield. “And there’s always something little that wants your attention. Sooner or later, you’re going to have a wire that breaks off and you’ll have to find it and solder it back on, or there’s flipper parts that wear out to the point where it’s no longer fun to play or actually doesn’t work.”

In the warehouse’s repair room, volunteers sort through pinball parts strewn on a long plywood table nearby. When in need of pieces that are no longer made, Schiess sometimes has to barter — learning how to bee-keep and gather honey, for example, for a man who, in return, could lathe a custom-built part. Twice a year, that process speeds up during visits from a pinhead named Christopher Nash, known in his hometown of Portland, Oregon, as “The Pinball Doctor.” In exchange for a bed at Schiess’ house, Nash comes because, for a pinball lover, he says, no experience compares with the Pacific Pinball Expo Schiess puts on every year in San Rafael. Last year more than 400 machines drew an international crowd of more than 3,000 in one weekend.

“I used to travel all across the country to different expos,” Nash said, while organizing pinball innards. “But there’s no point to that anymore. This show — it’s the cat’s meow of shows. It doesn’t get any better than this.”

The museum’s volunteer team is one of the reasons Schiess believes no other spot in the country can preserve or promote pinball as well as the Pacific Pinball Museum. The board of directors and team of more than eighty volunteers who help put on the Pacific Pinball Expo are a big reason Gordon Hasse decided to donate his collection to the museum.

“We weren’t rich, but we were dedicated,” Schiess said. “I think Gordon made the right choice because that’s the one difference that we have from the other people trying to do this. We’ve got a group that believes in this, and it’s a passion that drives us all to do this. There are more pinball museums popping up around the country now, and that’s great. What we’re afraid of is that all those are going to be temporary blips because they don’t have the kind of community support we do.”

Well, at least within their own pinball community. Schiess has given up on getting the City of Alameda’s attention regarding a bigger space for now. It’s possible that the museum might be able to expand into a storefront next door, which would at least make it big enough to host classes, exhibits, and more parties. It’s also located in the quirky, retro-business district of Old Town Alameda’s Webster Street, which is home to shops selling antique books, comics, vinyl records, and scuba gear.

The idea of possibly making the leap to San Francisco, if the Exploratorium decides to share its pier space with the pinball museum, is still up for discussion during board meetings. But in the meantime Schiess is going to try to grow the museum organically — for example, by trying to secure more academic grants to teach the science of pinball.

“We never moved ahead until it felt completely natural and easy to,” he said. “I think that’s been part of our success so far.”

There’s a lot that Schiess doesn’t know about the future of the museum. He has a respect for chaos theory, whether it’s in a pinball game or his own life. But no matter what, Schiess says he promises he’ll find a way to preserve the memory of his favorite game.

“I was joking with my wife the other day, and I was saying, ‘We’ve got to build a bunker way down deep in there, and build this infinity generator that can always generate 110 volts, and put a pinball machine in there,'” Schiess said. “When they dig through the rubble 2,000 years from now, they’ll find a pinball machine that’s still running, and they can figure out what the human race was all about.”