French intellectuals — what would we do without them? They make life interesting by making things complicated. An ordinary filmmaker/educator might bring a package of his or her favorite films to the Pacific Film Archive, all wrapped up with a harmless rubric of some sort — “Modern Times,” for instance, or “Orphans of the Storm” — and introduce one or two of them with a funny anecdote about what the movie in question, or the director, or the subject, means to him or her personally. And audiences would go away thinking what a swell fellow that is. Something along those lines.

But not Jean-Pierre Gorin. The UC San Diego film prof, who studied in Paris with Jacques Lacan and Michel Foucault, wrote criticism at Le Monde, collaborated on movies with Jean-Luc Godard, and moved to San Diego in the late ’70s to teach and make films about Southern California — he’s still there, doing that — does indeed have his own series of favorite films. He calls it “The Way of the Termite.” Originally organized by the Austrian Film Museum, the series is now poised to play the Pacific Film Archive in ten programs, beginning Thursday, January 22. Gorin will give three lectures following screenings as part of a residency at the PFA.

Subtitled “The Essay in Cinema,” Gorin’s group of nine features and as many shorts aims to challenge the ostensibly passive viewer, to set up a row of hurdles — not least of which is to locate the unifying thread that links, say, Luis Buñuel’s arch “documentary” about Spain’s poorest region with a BBC-TV exposé of international terrorism by CIA debunker Allan Francovich.

Gorin had the good fortune to teach at UC San Diego with Manny Farber, the monumentally influential critic and painter (1917-2008) whose book Negative Space, aka Movies, is one of the true indispensables of film writing. It was Farber’s 1962 piece “White Elephant Art vs. Termite Art” that evidently inspired his colleague Gorin to throw a net of meaning over the eighteen cinematic “essays” in the current series. In the book, Farber argued against the “square, boxed-in shape and gemlike inertia of an old, densely wrought European masterpiece” in films and paintings, and in favor of works that “seem to have no ambitions towards gilt culture but are involved in a kind of squandering-beaverish endeavor,” a “termite-tapeworm-fungus-moss art that … goes always forward eating its own boundaries, and, likely as not, leaves nothing in its path other than the signs of eager, industrious, unkempt activity.”

For Farber, the ideal cinematic “termite artists” included Laurel and Hardy, John Wayne (in The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance), Howard Hawks, and Akira Kurosawa, especially the latter’s Ikiru. The “white elephant” gang, on the other hand, always needed “to overfamiliarize the audience with the picture it’s watching,” a tactic that “serves to reconcile these supposed longtime enemies — academic and Madison Avenue art.” He cites François Truffaut, Tony Richardson, and Michelangelo Antonioni as particularly egregious early-’60s offenders, artists united, surprisingly, by fear — “a fear of the potential life, rudeness, and outrageousness of a film.” Extrapolating Farber’s analysis to the recent movie crop, we could point to Frost/Nixon, Valkyrie, and Defiance as white elephants supreme. The termites? Mickey Rourke in The Wrestler and Mike Leigh’s Happy-Go-Lucky — in that film, actor Sally Hawkins never stops chewing on her characters’ boundaries.

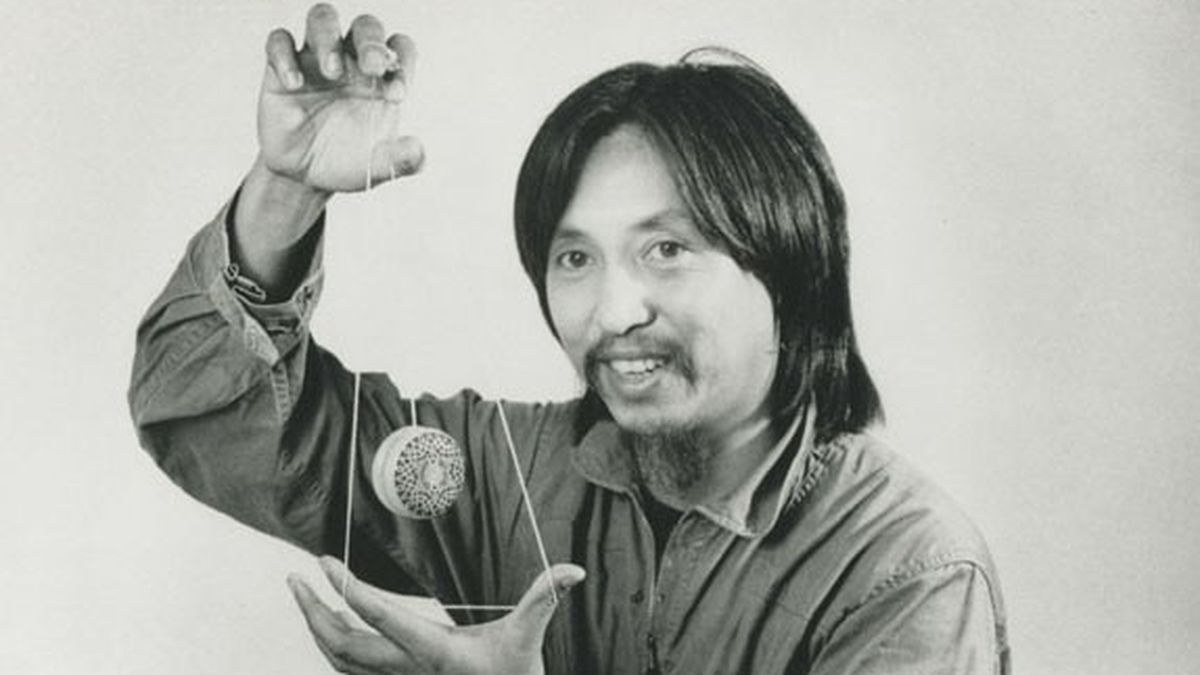

Gorin claims that the “unruly” version of the essay film on display in his collection “flirts with genres” but “attaches itself to none” in true Gerber termite fashion. Nevertheless, it’s no accident that almost all of the films in the series are straightforward documentaries, doctored docs, or faux docs — the only possible exception being Filipino writer-director Kidlat Tahimik’s staged re-creation of his own life story, Perfumed Nightmare.

After opening this Thursday, January 22 (7:30 p.m.) with Chris Marker’s Sans Soleil (1982), a typically oblique Marker meditation on Japan, San Francisco, Africa, and the space between (Farber would call it “negative space”), Gorin zings all over the map like a termite on deadline. Argentina in the late ’50s (Fernando Birri’s Tire dié) gives way to a D.W. Griffith editorial on unbridled capitalism (A Corner in Wheat, 1909); Buñuel’s proto-surrealistic portrait of utter desolation, Land Without Bread (1937); and Jorge Furtado’s 1990 examination of the Brazilian underclass, Isle of Flowers. From there, it’s a short hop to the USSR for Dziga Vertov’s wondrous The Man with a Movie Camera, a 1929 exercise in rat-a-tat-tat montage that somehow never loses its power to invigorate. Gorin and Godard admired Dziga Vertov so much they appropriated his name for their late-’60s collective, which produced at least five films, all brimming with leftist revolutionary zeal and stylistic abandon.

Whether Godard and Gorin’s Letter to Jane: An Investigation of a Still qualifies as termitic or suffers from “movement” elephantiasis is a question for another day, but that 1972 short feature remains one of the era’s most provocative political pieces. Movie star Jane Fonda visited North Vietnam during the “American War,” thus crossing the line between Hollywood and real life. She’s still defending herself over that. Gorin will explain it all in a lecture accompanying the January 31 screening.

One of the most absorbing docs in the series is Gladio, a three-part BBC public affairs mini-series in which investigative telejournalist and professional gadfly Francovich convincingly connects the dots of a frighteningly multifaceted plot by the CIA to stop the rise of communism in post-WWII Europe at all costs. Those costs included deadly terrorism made to look like the work of leftists, US military high jinks in Italy and Belgium, and massive amounts of disinformation, all paid for by the US and carried out by a shadowy “parallel army” of rightwing ops (SS “stay-behinds,” Fascist aristocrats, etc.). Francovich (1941-1997), maker of The Maltese Double-Cross, is the epitome of termitic diligence in his efforts to discredit US militarism. No wonder Gorin cottons to him.

But perhaps the best examples of Farber’s boundary-destroying energy are a pair of docs from Iran. The House Is Black by Forough Farrokhzad (1963) tours a leper colony in Tabriz with roughly the same dispassionate lack of overfamiliarization as Buñuel showed for the benighted residents of Las Hurdes. Moslem Mansouri’s Trial (2002) welcomes us to a dusty village near Tehran where the inhabitants are so in love with moviemaking they risk jail time (the state bans unauthorized filming) just to produce, act in, and view their own homemade movies on their favorite subject: themselves. What could be more termitic than that? They screen together on February 17. BAMPFA.berkeley.edu