In the year 2000, Stuart Alexander, owner of the Santos Linguisa Sausage Factory (and one-time mayoral hopeful) in San Leandro, shot three government meat inspectors, and attempted to kill a fourth, simply because they dared to come to his factory and try to inspect it. Not only did Alexander shoot the meat inspectors — one of whom was a grandmother — more than twenty times in his office in the middle of the workday, he also set up cameras to film himself doing it. That’s how sure he was that he was in the right, and that he would get away with murdering these vigilant “harassers” who tried to infringe on his lifelong privilege to do as he pleased.

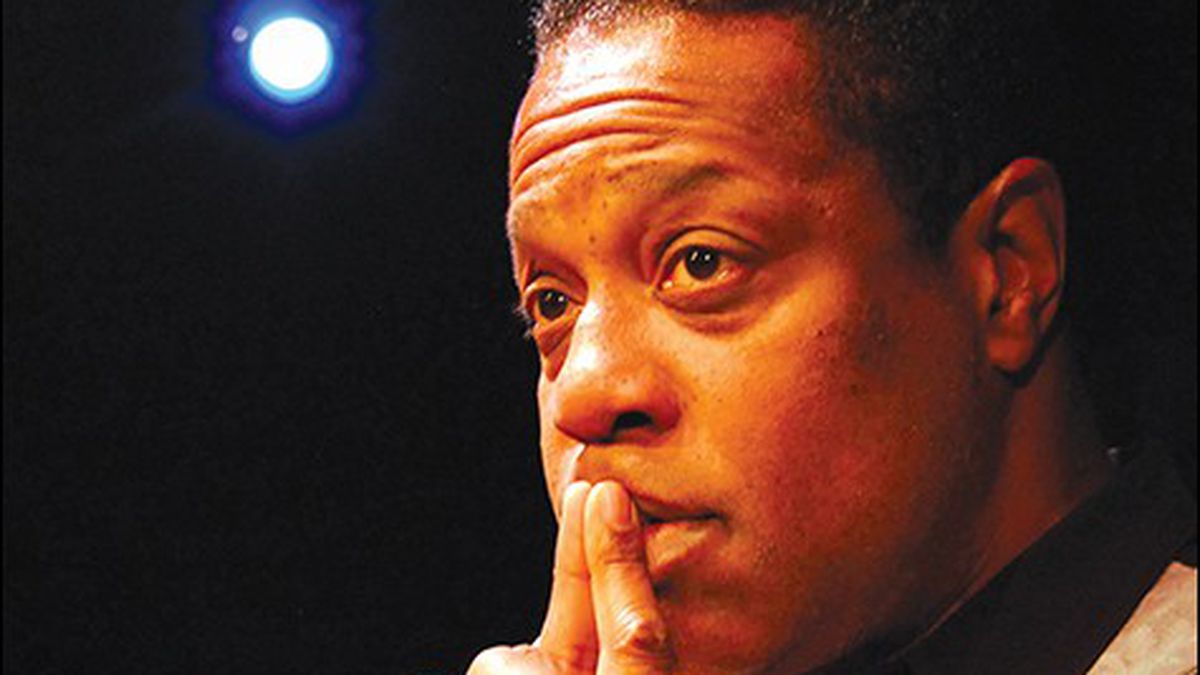

That’s the harrowing premise of Brian Copeland’s latest solo show, which is back at the intimate venue of The Marsh San Francisco once again (an earlier run occurred in February).

The East Bay often plays a role in Copeland’s solo shows — Not a Genuine Black Man detailed his childhood growing up in racially tense San Leandro, and The Waiting Period dealt with his lifelong struggle with depression and California’s mandatory ten-day waiting period for purchasing firearms. So, it’s not surprising that Copeland’s latest one-man show, The Scion, takes us back to the East Bay once again, this time not strictly as a personal narrative, but to recount the events leading up to the grisly San Leandro murders, and the power and privilege associated with people who believe themselves to be above the law.

Directed by longtime collaborator David Ford, Copeland’s retelling of the tragic events toes the line between the tragic and the comic. Though this show, much like Copeland’s previous efforts, deals with heady topics such as race and class privilege, profiling, police harassment, baffling politics (“Obamacare is slavery!”), and the murder of Trayvon Martin, Copeland is a master of wrenching the uglier aspects of American culture into entertaining and often enlightening endeavors.

Copeland intersperses personal narrative, court transcripts, police reports, testimony from friends and family of Alexander, and character sketches in order to paint a fuller picture of the slayings, and to answer larger societal questions such as how do we decide who’s dangerous, and why do certain people get special treatment.

In Alexander’s case, Copeland documents his track record of violence and run-ins with the law — a track record that is long, ghastly, and from which he received little to no punishment, despite, for instance, bashing in a kid’s head with a baseball bat and beating an elderly neighbor to within an inch of his life.

After Alexander shot the three USDA inspectors in his office, he came after the fourth, Earl Willis, who was waiting outside, and who, despite being chased and shot at, managed to escape. Copeland uses the example of Willis’ story to muse on the notion of racial privilege. Because Willis was African-American, witnesses mistakenly assumed he was the criminal — and not the victim running for his life.

Other poignant musings on privilege include Copeland’s own story of receiving free hot dogs and beer at a Giants game because the cashier recognized him and was a fan. Copeland humorously reflects on the irony of the situation. At one point, he said, he wouldn’t have been able to afford the exorbitant stadium prices, but now that he can afford it, he’s getting it for free. Why, he wondered, do we give special privileges to those who don’t need it?

Perhaps the most deeply felt example of Copeland’s reflections involves a story in which he and his son are driving around a roller rink parking lot, looking for a free space. His son complains that if only they could park in the handicap spot, it wouldn’t be an issue. Dad then explains that most of us exercise certain degrees of privilege, himself included, and why we have checks and balances in our society, which he illustrates with a metaphor: “Sometimes you’re the windshield, and sometimes you’re the bug — and we’ve got to do better for those folks who are always the bug.” As was the case of Stuart Alexander, we run into trouble, he reflected, when someone is the windshield too much of the time, i.e. when someone’s privilege goes unchecked for too long.

Though a few of Copeland’s characters were hard to follow and differentiate — sometimes the only distinction between characters was a subtle voice inflection change — his solo form is artful and his storytelling chops are as sharp as ever.