The orgy kind of comes out of nowhere. One minute you’re sitting in a well-appointed El Cerrito theater, watching opera, that highest of high arts — watching a production about a post-impressionist painter, no less — and then, all of a sudden, in the middle of the second act, there it is, bare bodies and a bare mattress onstage. It’s surprising, but then again, so are lots of things about Bonjour M. Gauguin, West Edge Opera’s excellent new show.

“This production is definitely a risk,” explained Mark Streshinsky, West Edge’s general director. It’s a word he uses a lot to describe the opera, which premiered in Venice in 2005, and the reason why becomes clear long before the orgy (which, by the way, is rendered with good taste and impressive grace). “We’ve found the piece to be complex, definitely difficult, but it’s a new sound that we hadn’t heard before,” he said. “This is definitely our out-there piece of the season” — which is saying something, considering West Edge has made a name for itself staging challenging work. “It’s very different from a lot of opera.”

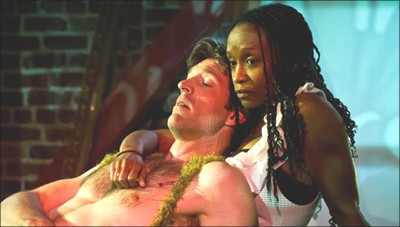

It is indeed. First off, the show, which Streshinsky co-directed with Yannis Adoniou, isn’t even really an opera, but rather a sort of hybrid multimedia work that incorporates modern dance (by Adoniou’s acclaimed Kunst-Stoff company), immersive video projection (by Jeremy Knight), and spoken text along with more traditional elements like instrumentation (performed by musicians from the local collective sfSound and conducted by Mary Chun) and singing (with Anders Froehlich in the title role, standout Shawnette Sulker as his inner voice, and three narrators).

It gets weirder. The libretto, or script, is what Streshinsky somewhat generously called “semi-narrative,” a collection of quotations from Gauguin and his contemporaries gathered to create a loose biographical narrative. The music, meanwhile — written by the Italian composer Fabrizio Carlone — Streshinsky deemed “not incredibly tuneful.” The orchestra is composed mostly (and unusually) of cellos, basses, and other instruments at the lowest-pitch end of the scale, which means there are none of the soaring violins or major lifts opera-goers (and music listeners) expect; all told, the effect is something like Debussy’s work, but possibly even more adventurous, marked by unexpected turns and atypical chord progressions. All songs are sung in French (though there are English supertitles); originally, the dialogue was, too, though Streshinsky ultimately decided “that would be too much of a barrier for people” and got it translated. There’s no traditional central love story; no set-piece dramatic sequence; not even, really a linear plot. There is, however: a monkey, light acrobatics, some biblical humor, a guy doing cartwheels across the stage unbidden.

Gauguin is dreamlike, introspective, and occasionally dark; unlike many operas, which traffic in big gestures and obvious themes, much of its tension is internal, with the main points of friction less about love and war and valor than ineffable, slightly eggheady, shades-of-gray concepts like ego, aesthetics, the self, and the nature of art. This is only the second time it has ever been produced, and the first in this country. “This is a totally unknown piece,” Streshinsky said. “Literally none of my colleagues in the new opera world have heard of it. It is definitely” — wait for it — “a risk.”

All of which is especially interesting — and important — given Gauguin‘s context. Opera, like the rest of the high-art world, was hit hard by the recession — small, local operas like West Edge even more so — and in an industry where one season’s ticket-holders pay for the following season’s productions, the aftershocks are still resonating. Because staging new work takes significant time and resources to develop, while well-known operas are nearly guaranteed to sell tickets, more and more companies are now turning to household names and repertory standards over work that may be more challenging, for both viewer and company. For that reason, last August, The New York Times all but declared a crisis for American opera, pointing out an “astounding conservatism” in the artistic ambitions of companies large and small. So when Streshinsky calls Gauguin a risk, he means that on not just an artistic level, but an existential one.

“There are many companies in this country that are sticking to the standards because they feel that their audience is very traditional and that’s what they want to see,” he said. “But we’ve always had a feeling and an understanding that audiences really become engaged through new work, and [we’re interested in] the idea of an audience coming to an opera and having an experience, rather than just sitting there.”

In a field where “new” work is often defined as having originated sometime in the last century, and where risk isn’t always rewarded, and where much bigger companies are pulling back, cutting corners, and doubling down on classics, what West Edge is doing feels downright, deliberately insurgent. But the way Streshinsky tells it, the company’s sense of adventure and its size are mutually reinforcing phenomena, and there’s a funny way in which the West Edge’s smallness allows it — and in some cases forces it — to dream bigger. For one thing, he said, companies of West Edge’s size have the freedom to plan and cast their seasons later; small companies also often have fewer sponsors and board members to answer to, fewer seats to fill, fewer dollars to worry about losing. “Really, the size of the company and being so small means we’re more flexible,” Streshinsky said. “It’s not really possible to do pieces like this unless you have that flexibility.”

And then there’s the truism that nothing breeds creativity like scant resources. “We’re not going to try to go head-to-head with the San Francisco Opera,” West Edge publicist Maura Lafferty said. “We’re two different cultures and artistic visions. And it’s a credit to Mark [Streshinsky]’s creativity that he can create really rich and vibrant productions with the resources he has.” Ultimately, for all its weirdness, Gauguin is truly a lean show. Because the orchestra is always the most expensive part of a production, and because Streshinsky bristles at paring down or thinning out a composer’s original work in order to cut costs, he specifically sought out an opera written for a small ensemble; Gauguin features just nine musicians. The costumes and sets are fairly minimal. The cluster of picture frames that sits toward the back of the stage came partially from PR coordinator Marian Kohlstedt’s basement. The show feels thoughtful — because it is, because choices are more intentional when resources are few.

So West Edge will never be able to stage large-scale, full-orchestra, household-name epics — like, say, Wagner’s nineteen-hour Ring cycle, which the San Francisco Opera produced in 2011 to nearly unmitigated praise — but then again, when Sulker’s bone-chilling soprano cuts in, or one of the Kunst-Stoff dancers moves in a certain way, or the orchestra begins a particularly, oddly beguiling section of music, that doesn’t really feel like a bad thing. West Edge has carved out a niche doing work that wears its extravagance in the form of imagination, though not necessarily execution; work that trades hugeness of production for hugeness of ideas; work that’s, yes, a risk, but a calculated one. Work that makes you wonder, work that might scandalize a few people, work that doesn’t have the benefit of a swelling string section or state-of-the-art pyrotechnics to tell you how to feel, and as a result, forces the audience to reckon with the music and the ideas on a deeper level. Work like Gauguin. Work in which the curtain call needs to be artificially extended so the dancers can get their clothes back on, but the applause is so loud and so long it doesn’t matter.