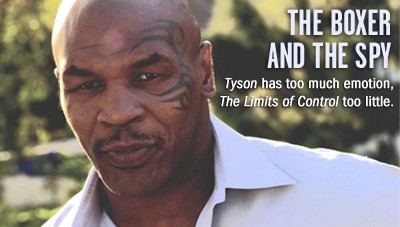

Even a person who knows nothing about the sport of boxing knows at least two things about Mike Tyson: 1) he bit someone’s ear and 2) he was convicted of rape. With the documentary Tyson, filmmaker and Tyson confidant James Toback manages to establish that the former heavyweight boxing champion is also a reasonably articulate man, for all his advertised brutality, and that he’s capable of reflecting on the morality of his life and career. Which means we’re in for a spectacle — the conscientious confessions of an ear-biter and rapist.

Well, yes and no. Toback’s 88-minute doc, featuring only Tyson’s talking head (gleaned from a reported thirty hours of video) plus archival news footage and no narrator or commentary, functions better as a first-person excursion into the mentality of a particularly vicious prizefighter than as an anguished mea culpa.

Tyson is onscreen for virtually the entire running time, and he tells his story in more or less chronological order, starting with his tough childhood in Brownsville, Brooklyn, raising pigeons (a movie cliché, but evidently true) and scuffling in the dope trade. That life changed when he began juvenile boxing in the 1970s with his mentor, fight manager Cus D’Amato, who told him he could be the next champion of the world. D’Amato, who had also handled Floyd Patterson, “trained me to be totally ferocious, in the ring and out,” claims Tyson. Fighting at 217 to 219 lb. at his peak, Tyson was admittedly not a big heavyweight, but made up for his lack of size with speed, accuracy, and power. He prides himself on having practiced “the art of skulduggery” and outthinking his opponents.

In 1986, at just twenty years old, Tyson KO’d Trevor Berbick for the heavyweight title to become the youngest-ever heavyweight champ. Thrilling bouts with Michael Spinks, Buster Douglas, and Evander Holyfield followed (Holyfield lost a piece of his ear in their notorious second matchup), but Tyson’s troubles outside the ring overshadowed his fistic accomplishments. Want to rile him up? Just say the name “Don King.”

By age twenty, Tyson had also married movie star Robin Givens, contracted gonorrhea, and become “intrigued by sex.” By his own admission, sex and violence mingled in his mind as twin battlegrounds in which he must prevail or die. After his conviction for raping Miss Black Rhode Island, Tyson spent three and a half years in prison, where he became a Muslim and acquired tattoos of Mao Zedong and Che Guevara. He also, in his estimation, “became more humble and subservient.” The forty-year-old we meet on camera lays on the self-pity — “Old too soon, smart too late” — and maintains he’s tired of fighting: “I don’t have this in my heart anymore.”

Like Norman Mailer before him, writer-director Toback (Fingers, The Pick-Up Artist) seeks nobility of character in blood sport. Toback is looking in the wrong place. His subject is soiled. Tyson is a creep — a seemingly contrite, surprisingly introspective creep with a hard-won sense of irony, but still a creep. He’s candid, in his way, about his brutal outlook on life, but candor alone can’t redeem him. He “lost his composure” with the ear-biting thing and saw the violent conquest of women as a continuation of his struggle to survive, he tells us. But there’s no opposing point of view in the film.

Toback presumably wants us to see Tyson as a product of his times, but we can’t really buy that because, after all, we have Muhammad Ali, who was everything Tyson was not. Mike Tyson, the anti-Ali, may indeed be a tragic figure worthy of Greek mythology (the way the film’s publicity touts him), but if so he’s more akin to one of those accursed, grotesque mortals punished by the gods for daring to reach too high. Tyson, one of the most pathetic of documentaries, deserves to be his epitaph.

How to make a Jim Jarmusch spy thriller: Have an actor (Isaach De Bankolé, of the striking African face) move mysteriously around various sites in Spain, dressed in impeccable European suits and saying almost nothing, seemingly waiting for some signal to spring into action. And that signal never comes. That, gentle reader, is the setup for Jim Jarmusch’s The Limits of Control, the latest indication that Jarmusch, once (twenty years ago) the darling of the art house, has painted himself into a nasty, frustrating corner of his own devising.

Jarmusch’s most successful entertainments — Stranger than Paradise, Mystery Train, Dead Man, Ghost Dog: The Way of the Samurai, Broken Flowers — have all been significantly underwritten, but the aptly titled Limits carries that concept to unbearable heights in the story of De Bankolé’s nameless character, forever ordering a pair of espressos in separate cups and encountering a succession of similarly adrift actors as they float through Madrid, Almería, and Sevilla, exchanging matchboxes. Each new matchbox contains a tiny note, written in code, which De Bankolé promptly eats after reading. He eats many of these, in many places, until he finally gets to a blank note. Aside from his final scene with Bill Murray inside a guarded complex in the countryside, the ritual with the notes is probably the high point in terms of narrative incident. Such are the lengths to which an apparent fascination with Michelangelo Antonioni can carry one.

But even Antonioni had motivations for his characters, however obscure. Here, our only clues about the Nameless One and his mission come from the vague, improvised-sounding repartee between him and the Woman in White (Tilda Swinton), the Mexican (Gael García Bernal), the Man with the Guitar (John Hurt), et al. The action is so shamelessly padded, so devoid of emotion, that we’re relieved when our spy happens into a late-night tablao flamenco rehearsal and we’re treated to some actual, spontaneous personality.

What could Jarmusch be thinking? Perhaps the bespectacled, nude woman who seems to follow the spy from place to place (Paz de la Huerta) holds the key — her derriere speaks volumes. Maybe the title is part of some interactive game Jarmusch is playing with his audience, as in: Try to control yourself while watching this movie. Well, we give up. Limits is nothing more than Jarmusch’s worst film since Night on Earth. The spy does have nice clothes, though.