It is just after 7:00 p.m. at East Oakland’s Foothill Square bingo parlor, and at least 150 people occupy the hall’s sea of banquet tables. Most find their way here weekly or even nightly. They wear game faces and wield arsenals of bingo-themed accessories: colored daubers, blinged-out seat cushions, and sizable rolls of cash. Some will drop $500 dollars tonight. Others will invest only the minimum $15. In both cases, they’re hoping for a return on their investment. But if they lose, at least they know their money is going to a good cause.

California law requires that bingo games be run by nonprofit organizations that donate their profits to charity. And from the looks of things at Foothill Square, that’s what’s happening here. Polaroids of smiling children line the walls, and a banner overhead credits the smiles to the parlor’s two nonprofit bingo operators, Kids Educational Development Scholarships and Breast Cancer Development and Research Society. Rows of framed letters on city letterhead sing the two groups’ praises. “We truly appreciate Kids Educational Development Scholarships’ continued generosity and we thank you for helping us,” reads one from the Children’s Hospital in Oakland.

At Foothill Square, photos of children suggest the operator’s charitable intent. Credits: Maya Sugarman

Smart players play as many cards as they can afford. Credits: Maya Sugarman

Landlord Robert Casteel III earned $70,000 a month in rent at Foothill Square in 2006. Credits: Maya Sugarman

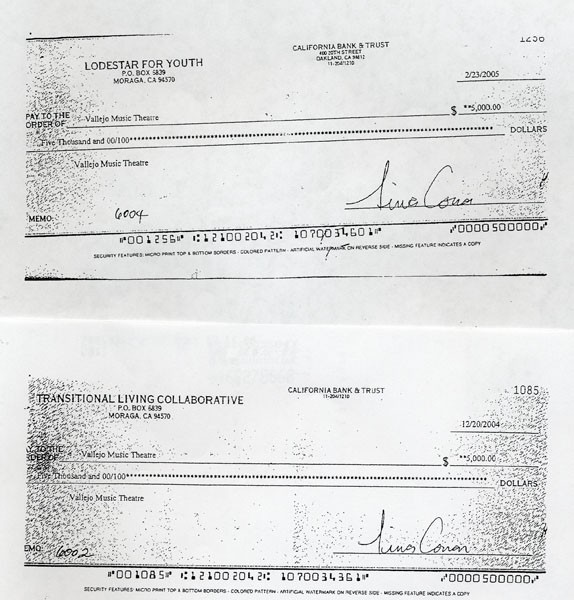

When Robert Casteel (right, in a photograph from his web site) paid Brown with checks from two nonprofit groups in which he was not supposed to have a financial interest, that raised her suspicions. Credits: Chris Duffey

Barbara Killey hopes to see Oakland tighten its regulation of bingo parlors.

But what most players here don’t know is that little of their money is going to charity. Instead, it goes straight into the pockets of a few savvy entrepreneurs who are making big money on charitable bingo. According to federal tax returns and City of Oakland reports, only about 3 percent of Foothill Square’s revenue ever finds its way to charity. After prizes are doled out, most of the remaining revenues end up with the parlor’s operator or the vendors who provide it with supplies and equipment.

Since its long-gone days as grandma’s favorite pastime, bingo has evolved into a serious money-making machine. When California’s current regulations became law in 1976, bingo games were mostly small, low-stakes operations in church basements and high school gyms. Then operators discovered that bigger venues, more frequent games, and new gaming technology could produce larger revenues, and a host of giant facilities entered the field. Where low-stakes weekly games yield annual revenues in the tens of thousands of dollars, larger nightly operations can rake in tens of millions.

Genuinely charitable bingo operations still exist, but they’re being crowded out of the field by a new class of profit-oriented parlors. Loopholes in the law line up to accommodate for the industrious. But sometimes the industrious push the envelope. An illegal bingo operation can be hard to spot, but there are definite warning signs, according to “Dr. Bingo,” Ronald Rickey, who consults to charities with gaming operations. If an operator’s costs resemble their revenues, if their tax forms are full of holes, or if their “volunteer” staff has actually been working there for years, their motivation may not be charitable. California law requires bingo operations to be staffed by unpaid volunteers. But, as Rickey observes, “I can’t think of anyone who would want to spend all of their time and energy on running bingo without getting some kind of compensation.”

Bingo has become a cash cow for “cottage industry” entrepreneurs because no federal guidelines dictate how charities must spend their money. Operators can pocket as much as 99 percent of their income and still be considered legitimately “nonprofit.” Not surprisingly, just as large parlors began cropping up all over California, a host of new “nonprofits” also emerged, citing bingo as their sole fundraising activity. These tend not to resemble your average Rotary Club. Instead, they are foundations that act like a middle-man, collecting money and then doling it out to charities of their choice. Sometimes these charities are linked to the operator of the bingo parlor, in possible violation of the law.

Legitimate charities that once relied on bingo for fundraising are suffering from competition of this type. But some are fighting back. In 2006, a consortium of small nonprofit groups in Vallejo sued their landlord, Robert Casteel III, who operates bingo parlors in Vallejo and Oakland. The nonprofits accused Casteel and his Cornucopia Ventures of illegally enriching themselves by passing bingo proceeds through a handful of fake charities under his control. Although the case was dismissed before the charges were resolved, the lawsuit sheds light on several aspects of Casteel’s Oakland operation at Foothill Square.

Welcome to the world of charitable bingo, which often isn’t very charitable. But paltry donations are just the start of the story. Public records also show that Oakland’s largest bingo operations all exceed the state’s monthly cap on overhead costs, report very different finances to the city of Oakland and the Internal Revenue Service, and operate electronic equipment that will soon be illegal. These offenses appear to violate federal and state laws and city ordinances. But that doesn’t seem to matter, because enforcement agencies seldom pay attention to the seemingly innocuous game of bingo.

That’s why Judith Brown decided to take matters into her own hands.

Brown’s nonprofit organization, the Vallejo Music Theatre, fell into bingo in 2002 when it decided to buy a historic downtown building for a performance space. Retrofitting costs would be high, and managing director Brown knew the theater couldn’t afford the project without a reliable fundraising source. So when her acquaintance Gregory Brennan offered to run twice-weekly bingo games at Casteel’s Triple Seven bingo parlor, Brown jumped at the chance.

Brennan knew about bingo through his acquaintance with Casteel, who not only leases bingo parlors but also manages a battalion of companies involved in insurance, spas, real estate, and bail bonds. The links between Casteel’s Vallejo and Oakland operations first came to light in reporting by Alex Gronke on the web site Novometro.com.

The theater rented out the parlor two nights a week and initially paid Casteel $1,100 per night, Brown said in a recent interview. Everything went smoothly for a while. But the more money the theater made, the more its rent crept up, until Brown alleged in court that he was charging the charities in his hall up to $2,600 per night in rent.

Brown eventually replaced Brennan with Chester Piet, who had managed bingo games at Triple Seven and Oakland’s Foothill Square for other groups. Piet said Casteel kept raising the rent because he saw how much money his tenants were raking in. “He said if they complained just to tell them that he’s the landlord and that’s what landlords do,” Piet indicated in a written statement.

And complain they did. Brown went to the Vallejo police department and formally complained that Casteel was driving her theater out of the bingo business. But city officials didn’t pursue the matter. In the meantime, Casteel collected a killing in rent. In his statement, Piet described delivering up to $10,000 in cash each week to Casteel’s Concord spa.

Casteel eventually kicked out the theater and his other tenants and replaced them with three of the groups running games in Oakland: Lodestar for Youth, Transitional Living Collaborative, and Breast Cancer Development and Research Society. In exchange for being evicted, Casteel began paying the theater $5,000 a month to help out with its mortgage.

Brown noticed that the checks came from the very charities that had displaced her theater and the other tenants. She took this as a sign that Casteel was illegally involved in the finances of his supposedly charitable tenants. According to state law, it is a misdemeanor for any person to receive or pay a profit, wage, or salary from any bingo game, and the Vallejo city ordinance forbids operators such as Casteel from having a financial interest in the charities that rent their parlors.

After five months, Casteel informed Brown that he would no longer be sending her any checks. “I’ll never forget that conversation,” she said in an interview. “He told me that he needed the money to buy goats for starving people in Zimbabwe.”

Once they were booted out of the Triple Seven, Brown and her theater group tried to run their own games at a local Elks Club. They ran games once a week for twelve weeks, and got their supplies from a supplier in Los Angeles because none of the local suppliers would sell to them. Brown alleged in court that local suppliers were threatened by associates of Casteel who said they would pull their orders if the suppliers sold to Casteel’s competitors. But supplies were expensive to ship from Los Angeles, and the theater couldn’t afford it. Brown also alleged in the lawsuit that on nights she tried to run games at the Elks Club, Casteel’s tenant at the Triple Seven would lower its prices from their normal $35 “buy-in” down to $20. “Nights they ran those prices, they had a full house,” Brown said.

In 2006, Brown’s theater and some other nonprofit groups sued Casteel and two of his companies, along with the three nonprofits running games at Triple Seven. They accused Casteel of creating fraudulent nonprofit groups willing to illegally pay the exorbitant rent he was charging so that he could appropriate bingo proceeds for non-charitable purposes. All of the charitable groups that ran games from Triple Seven claimed that they were unable to use their most successful form of fundraising because Casteel had monopolistically closed the bingo market to other organizations.

The lawsuit alleged that all of the nonprofits running games out of the Triple Seven shared a post office box in Moraga that was rented by Casteel. They also listed the phone number and address of Casteel’s office in Martinez as their contact information. None of the nonprofits appear to have public phone numbers, web sites, or physical addresses to confirm their existence. And according to court records, all of the “volunteers” working the parlor floor happened to be Casteel’s relatives or employees of hisbail bonds business. In court records, one of his employees admitted to working forty hours per week as a bingo hall manager. “That’s what they do,” Brown’s lawyers said. “They run these charities for Casteel and they get paid for it.”

In a recent phone conversation, Casteel declined to answer questions about the lawsuit and hung up before he could be asked other questions. However, attorneys for him and the other defendants argued in court that the allegations were false, and lacked evidence.

But the California Secretary of State’s office indicated that, two months after the lawsuit was filed, Casteel cancelled his state registration for the implicated companies. And one month after that, according to the charity’s minutes, all three nonprofits held meetings on the same date at Casteel’s office in Martinez in which their boards voted to remove him as a signer on their accounts.

Nonetheless, a judge in Contra Costa County Superior Court dismissed the lawsuit in early July. The judge ruled that only cities and district attorneys have the jurisdiction to challenge violations of a city ordinance. Brown’s attorney has taken up the matter with the city of Vallejo, and says he plans to keep working on the case.

But he is having a hard time implicating Casteel in any illegal activities. Charging high rent is not illegal. Neither is having friends or even employees running games on the parlor floor — as long as they are not employed by the nonprofit running the bingo game. Even if Casteel was involved in the charities running games at his parlors, it would be difficult to prove that he had a financial interest in those charities without a detailed exploration of his and their finances. As for the other defendants, they argued in court that the “monopolistic” behavior they were accused is lawful in California.

Finally, the state’s $2,000-a-month overhead limit came up in court, but it worked against Brown since it was the theater company, and not Casteel, that was actually breaking the law. In a recent interview, Brown said Casteel’s lawyers asked her why she paid high overhead costs for rent and supplies if she knew it wasn’t legal. “I told them that we had no choice,” she said. “If we wanted to have a bingo game Vallejo, we had to pay.”

The East Bay hosts four of the state’s largest charitable bingo parlors, Bingo Arcade in Pleasant Hill, Gilman Street in Berkeley, and two located about a mile from one another in East Oakland, at the Foothill Square and Durant Square Shopping Centers.

At Casteel’s Foothill Square’s parlor, Breast Cancer Development and Research Society rents out the parlor five nights a week and Kids Educational Development Scholarships rents it out the other two. Besides sharing parlor space and a few security guards, KEDS representatives insist that the two nonprofits are unrelated. At Durant Square, a nonprofit called Community Charities rents out the parlor space seven nights a week. Combined, those two parlors see annual revenues of more than $15 million, according to city reports.

Not far from the parlors at Durant and Foothill, the East Oakland Senior Center runs the only Oakland bingo operation that doesn’t use electronic equipment and doesn’t operate out of a parlor. Director Leroy Slaughter said his center doesn’t even try to compete with the larger parlors. Even though he knows his center could make big money if it really wanted to, he said the center’s bingo committee decided that bigger games with larger stakes might draw a “bad crowd.” Instead, they choose to run games once a week in the middle of the afternoon, which keeps their crowd limited to around fifty players a week, 95 percent of whom are seniors living in the building.

Slaughter says most of the seniors living there couldn’t afford to pay for higher-stakes games. “I think that the seniors play here because even if they lose, they know that they’ll see their money later,” Slaughter said. That’s because all of the proceeds go directly back into the center to pay for organized activities, which include occasional field trips to museums, flea markets, and other nearby attractions. “The city doesn’t give us any money for activities,” he said. “So we have to raise all of our own funds if we want to organize anything.” But the games themselves are only partially for fundraising. “We run games mostly as entertainment,” he said.

Because the center doesn’t have to pay rent, most of its overhead goes to supplies. According to its monthly report to the city, in June it made $4,002 total, paid out $3,160 in prizes, and spent $638.29 on “miscellaneous” expenses like security and supplies. Their total profit for the month came out to $203.46, which means roughly $2,240 for the whole year. (It doesn’t operate in August.)

Ulysses Cooperwood, who manages Berkeley’s Gilman Street bingo parlor for the nonprofit Phyliss Elena Parker Foundation, says bingo is a high-expense activity. The parlor where he runs games is small compared to Oakland’s giants, but he said he still pays rent of about $2,000 a night. And because his games have already built up a reputation at that location, they can’t just get up and move somewhere else. Mary Parker, who used to work at Gilman Street Bingo but now runs the Parker Foundation, said competition from other parlors and Indian casinos has led to tough times in her industry. “Bingo is not that good right now,” she said in a recent phone interview. “A lot of organizations have pulled out.”

Differences between city bingo ordinances probably account for why some cities have parlors and others don’t. For instance, Alameda’s municipal code prohibits the lease or rental of any gaming equipment. Such equipment comes in the form of both paper supplies, like bingo cards, and electronic equipment, like hand-held devices that can keep track of hundreds of cards simultaneously. These days, a bingo parlor without electronic equipment just can’t compete with the big parlors, which is probably why Alameda boasts just one tiny bingo game, at a senior center. This regulation also prohibits the arrangement that some parlors use to get around the ban on paying employees. For instance, Chester Piet revealed in the Vallejo lawsuit that he received wages directly from the manufacturers who sold supplies to Casteel.

But if bingo is not that good for small operators, it’s still very good for the big parlors. According to a report from the City of Oakland, the two charities operating at Foothill Square — Kids Educational Development Scholarships and Breast Cancer Development and Research Society — paid Casteel’s Cornucopia Ventures a combined total of nearly $70,000 a month in 2006, which far exceeds the state’s $2,000 a month overhead limit. According to city records, this came out to $2.79 per square foot. Meanwhile, city records showed that Casteel himself was only paying $.95 cents a square foot for the property.

The charity operating at the Durant Square bingo parlor, Community Charities, paid nearly $50,000 per month, almost twenty five times the legal limit. Durant Square property representative, Roger Huddlestone, said his company charges $3 per square foot per month for the space at Durant Square, which is on par with fair market value. “Keep in mind that this is a full-service facility. That means we pay for cleaning, utilities, water, the alarm system, equipment, chairs, tables, phone bills, and more,” said Huddlestone. But Linda Braz, Director and Senior Project Consultant for Metrovation Brokerage, a commercial real estate firm in Oakland, said that anything above $2.50 per square foot per month for retail property in East Oakland is unreasonably high. “We’re looking right now at trying to get $2.25 per square foot in Old Oakland, which is a much nicer piece of property,” she said.

The high cost of rent may explain why Community Charities donated a mere 2.7 percent of its $5.4 million revenue in 2007, according to tax forms. Some of its donations have gone to Oakland’s schools, but over the past two years, a large chunk went to two main groups: the Oakland Police Activities League ($108,500), and a group called Bay Area Charities ($15,600).

Bay Area Charities does not have a web site or phone number, but public records indicate that the nonprofit is located at the same Pleasanton address as Bay Area Commercial, Inc., which is the real estate company that leases the parlor for Community Charities. Roger Huddlestone, representative for Bay Area Charities and Bay Area Commercial, says Bay Area Charities went defunct two years ago and has not been getting money from Community Charities. However, the group’s tax forms indicate that it gave more than $15,000 to Bay Area Charities in the past two years. H. Clyde Long, a lawyer for Community Charities, said to his knowledge the charity still exists.

Community Charities isn’t Oakland’s only operator with a less-than-impressive charitable record. According to 2006 tax records, Kids Educational Development Scholarships only donated 2 percent of its $1.4 million revenue that year.

Such high costs are not illegal. But reporting false tax information to the city or the Internal Revenue Service is, and at least three of Oakland’s biggest charitable bingo operators may be guilty of that. In 2006, all three nonprofits running games out of Oakland’s two bingo parlors reported different financial information to the city than to the Internal Revenue Service. Kids Educational Development Scholarships told the city it earned $5.2 million in income and spent $166,083 of that on donations. But its publicly available tax forms claimed revenues of only $1.4 million and donations of $26,956.

Lori Adragna, who manages Kids Educational Development Scholarships, attributed the discrepancies to the lack of uniformity between how the city and the IRS require nonprofits to report their finances. For instance, Adragna reported income for the game “Flash Tickets” on her monthly financial reports to the city, but not on her tax forms. City reports indicate that the IRS recently deemed this income taxable, and both Kids Educational Development Scholarships and Breast Cancer Development and Research Society are now paying back taxes for those sales as a result. Adragna insists Kids Educational Development Scholarships has nothing to hide. “We were just audited for 2004 through 2007 and had no problems,” she said in an interview. “We were found to be 100 percent compliant.”

Community Charities told the city it made $5 million and spent $135,600 on donations, but tax forms claimed earnings of $5.5 million and donations of $138,100. And Breast Cancer Development and Research Society told the city it earned $4.1 million in income and spent $562,150 on donations, but its tax forms claimed only $2.6 million in income and $470,700 on donations. The breast cancer society also failed to notify the IRS that it contributed $5,000 to former assemblyman Fabian Núñez, who noted the contribution on his disclosure forms.

Donations of this size might seem large to a casual observer, but they accounted for less than 1 percent of the revenue of Oakland’s bingo halls that year. They certainly seem small to Barbara Killey, the City of Oakland hearing officer who oversees the city’s bingo scene. “What immediately struck me as strange were the donations going to places that weren’t actual registered nonprofits and the amount that bingo operators were paying for rent,” she said in a recent interview.

Killey issues annual permits, collects and checks financial information for nonprofit operators, and compiles annual reports that she presents to the city council. When she assumed her position in 2004, she concluded that her predecessor’s oversight was lax and that his reports focused primarily on praising bingo operators. “In 2003, bingo operators contributed $108,699 to assist Oakland citizens who had no other available community resources to help them,” read one such 2004 report. “This contribution to citizens of a disadvantaged community was a tremendous social equity and benefit for the City of Oakland.”

She also quickly concluded that the rents being paid to parlor operators such as Casteel exceeded what was permissible under the law. She spoke with the Alameda County District Attorney’s office about this issue during her very first month on the job. Although she does not recall specifically who she spoke with, she said the prosecutor told her “that $2,000 per month, the limit established when the ordinance passed, is not reasonable. So that aspect of the law has been overlooked.”

In an interview, Alameda County Deputy District Attorney Thomas Rogers said he hasn’t heard any complaints about local parlors since the late ’70s. He said if his office had received complaints, it would have referred them to the Oakland police, who would have decided whether or not to investigate. “The police do the investigations and then they bring it to us,” he said. Oakland police representatives said that they haven’t received any complaints about the parlors in recent years.

In fact, law enforcement generally ignores bingo-related crime because it’s less pressing than other crimes, not to mention legally complex and time-consuming to investigate. The law leaves enforcement in the hands of police and district attorneys and gives cities the option of supplanting state regulations with their own ordinances. But cities also are often reluctant to dig too deeply into bingo because schools, hospitals, and law enforcement often benefit directly from charitable donations. “There’s a legitimate amount of money going to charities that wouldn’t otherwise be going there,” Killey said. “In the case of the city, we don’t want to shut that down.”For example, city reports indicate that in 2006 Breast Cancer Development and Research Society donated $100,000 to one of Oakland city council member Larry Reid’s pet projects, Youth Uprising, and donated another $150,000 to other East Oakland-based charities.

But in recent years Oakland has received fewer donations from charitable bingo operations than it would like to see, and now the city is thinking more seriously about enforcing the law. According the most recent city report on bingo activities, donations in 2007 went down 40 percent from the previous year. The report suggests that donations may have decreased because of “increases in expenses disproportionate to the increase in gross income.” In order to really understand where the money is going, Killey says she needs to see more detailed financial information from the parlors.

Requiring annual audits of bingo parlor landlords and the nonprofits that rent their facilities is just one of a slew of addendums to Oakland’s bingo ordinance that Killey has proposed to the city council. She also recommends that the city require bingo operators to pay a monthly law enforcement fee to account for police services, that 90 percent of charitable bingo donations be spent within city limits, and that parlor rental fees not exceed “fair market value.” Killey says she’s looking into what “fair market value” would be for bingo parlors in that area. Changes of this type could have serious consequences for Oakland’s bingo parlors. Killey already shut down a parlor in Fruitvale last May because it was spending all of income on overhead and none on charity.

A June meeting of the Public Safety Committee suggested that the city council might be on its way to approving Killey’s addendums. At that meeting, councilwoman Patricia Kernighan referred to exorbitant rents at parlors as “a gigantic loophole subject to abuse.” Councilwoman Jean Quan expressed grave concerns that, “out of $15 million coming mostly from low-income people in East Oakland, only about 3 percent of that is going back to any sort of charitable institution.” Councilmember Larry Reid, whose district contains the Foothill Square and Durant Square parlors, was the only council member to defend parlor operators. Still, he agreed with others that both landlords and game operators should be audited regularly, on their own dime.

Casteel’s attorney has written Killey that under his interpretation of state law, the city can’t legally implement any rent caps at the Foothill parlor. If the city can’t find any way around this and parlor operators aren’t willing to lower their rental rates, nonprofits running games out of Oakland’s two largest parlors may be forced to find somewhere else to host their games. All of these issues and more are sure to come up at the October 28 meeting of the Public Safety Committee.

Brown hopes the city of Vallejo will follow suit. If they don’t, she worries that bingo parlor operators like Casteel are going to continue taking advantage of the system. “They found a cash cow,” she said. “And they’re going to milk it for all they can get.”