If the Oakland music scene needs a cheerleader, it may very well come in the form of a strong-jawed, swift-talking, tattooed punk-rocker. Damon Gallagher is probably the first to admit that he’s not exactly a rah-rah type, but get him talking about the East Bay’s musical landscape — and its myriad challenges — and it’s clear that he is personally invested. Slightly obsessed, even.

It’s why Gallagher has been playing the scene for several years as part of Damon and the Heathens, and it’s why he opened Vitus, a massive Jack London restaurant and music venue, in September. “We have more venues than ever, better venues than ever before, and a serious community spirit,” he said, sitting in his upstairs office at Vitus as sounds of the rehearsal for that night’s act — a bracing neo-soul ensemble — wafted through the open door. “People are excited to be going out in Oakland, excited to be seeing music in Oakland. I really feel like this is the place to be right now.”

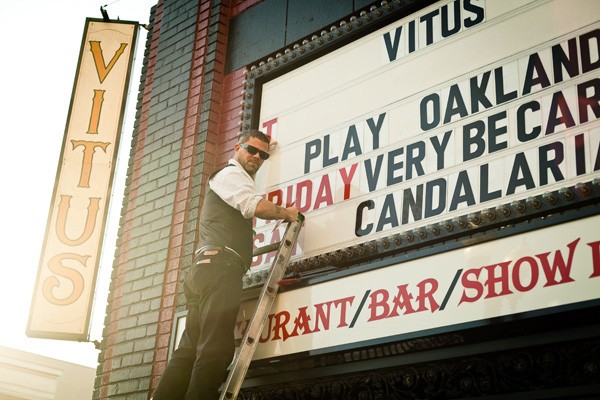

Damon Gallagher, owner of Vitus, says radius clauses that prohibit bands from playing in the East Bay are hurting Oakland’s music scene. Credits: Stephen Loewinsohn

Gallagher opened Vitus last year. Credits: Stephen Loewinsohn

Yoshi’s, which recently featured a show with Ray Manzarek, can book acts at both its Oakland and San Francisco venues.- Credits: Stephen Loewinsohn

The Tenderloins played a recent gig at Vitus in Oakland. Credits: Stephen Loewinsohn

Vitus is building its reputation on booking edgier, more up-and-coming acts.. Credits: Stephen Loewinsohn

He’s got a point. In the last few years, the East Bay — especially downtown Oakland, once a veritable ghost town at night — has seen a near-explosion of dance clubs and music venues, including Vitus, The Layover, The Uptown, Disco Volante, The New Parish, and the refurbished Fox Theater. At the same time, with the arrival of pedigreed new bars and restaurants like Plum, Make Westing, Bar Dogwood, Rudy’s Can’t Fail Cafe, and Xolo, Oakland’s cachet as a regionally-recognized drinking and dining center has grown, and the city now has the infrastructure to support hungry and thirsty concertgoers.

Civic investment in redevelopment and public safety made Oakland a more attractive nightlife destination, and the Broadway Shuttle — which runs free from Uptown to Jack London Square until 1 a.m. Friday and Saturday nights — has made it more accessible. At the same time, the Great Recession has prompted cavalcades of young, hip, creative people to give up their Mission and Lower Haight flats for Uptown apartments and West Oakland warehouses. Several nationally known hip-hop, garage rock, and electro-pop bands also have come out of Oakland in recent years. All told, this is the East Bay’s moment for a live-music renaissance.

Except there’s one big, institutional obstacle to creating the kind of destination music scene that Gallagher and his peers envision: Many music acts are simply not allowed to book shows in Oakland.

The reason has to do with the little-known, behind-the-scenes process that governs where musicians play and when. And in the Bay Area, San Francisco rules. Most San Francisco venues, in fact, require acts to sign a contract stating that they won’t play elsewhere in the Bay Area within a prescribed time period. It’s known within the industry as a radius or territory clause, and it’s arguably one of the biggest shapers of the Bay Area’s musical topography, influencing which bands book where — and, by extension, which clubs succeed and fail, which neighborhoods capture popular and media attention as anointed “destinations,” and which cities’ economies get the benefit of money spent on food, drinks, and tickets.

A radius clause also can be unfair to artists, because it strips bands of the power to determine their own fanbase.

Proponents of radius clauses, however, say they’re necessary to balance supply and demand, especially as the live music industry continues to sustain the aftershocks of the recession. After all, this is still a business, and in order to stay afloat, clubs and concert halls need to be sure that an act they book won’t show up on the other side of the bay playing for half the ticket price. Besides, a half-filled show isn’t good for the venue, performer, or audience.

But from another perspective, radius clauses are unfair at best, opportunistic at worst, and in some cases, borderline illegal: In 2010, Illinois State Attorney General Lisa Madigan investigated Lollapalooza promoter C3 Presents for anti-trust violations after it tried to impose an outlandish radius clause that barred bands from playing within three hundred miles of the festival’s site in Chicago. What’s clear is that these arcane rules fundamentally privilege bigger cities over smaller ones and raise questions about the limits of fair competition.

Or, at the very least, they put Oakland at a systemic disadvantage — especially when it comes to touring bands. If you ask Gallagher, it’s something of a no-brainer: Acts that are unfamiliar with the Bay Area are almost always going to choose the bigger, brand-name city over the smaller, scrappier one, leaving Oakland venues with fewer options.

Even bookers who don’t have a vested interest in one side of the bay over another acknowledge this. “When you’re a small club act on tour and you have to pick one place to play in the Bay Area, you’re gonna pick San Francisco,” said Allen Scott, executive vice president at Another Planet Entertainment — which books venues including The Independent, The Fox Theater, The Greek Theatre, and the Bill Graham Civic Auditorium, as well as the Outside Lands and Treasure Island music festivals. “It’s just a reality.”

As a result, East Bay venues are, by and large, forced to settle for lower-quality and lesser-known acts — or the bands themselves are forced to violate their contracts and play in Oakland anyway. “I can’t tell you how many friends’ bands I’ve had coming through who weren’t reading their contracts or who maybe had to go through their label, and they had to either sneak around and play secret shows, or just not play Oakland at all,” Gallagher said. “It definitely hurts.”

Though the specifics vary, at their core, radius clauses are designed to prohibit artists from two-timing — that is, playing multiple stages within the same market in a certain period of time. Traditionally, the industry standard has been “ninety days, ninety miles” — that is, acts are barred from playing within a ninety-mile radius for three months before or after a show. That’s what many big music presenters still use, though Another Planet employs a sixty-days-sixty-miles standard, and the contract language at Slim’s and Great American Music Hall eschews mileage specifics altogether and simply bans double-booking within “the Bay Area,” including some, but not all, parts of northern Marin County. Essentially, though, Oakland, San Francisco, Marin, and San Jose have long been treated as a monolith, as though the entire Bay Area were one single market for music.

For Oakland, which is just beginning to establish itself as a place with a vibrant downtown, this means venue owners have a much harder time convincing booking agents to choose their clubs over the ones in San Francisco. New Parish owner Michael O’Connor, who opposes radius clauses as a rule, said he constantly has to prevail upon band managers and agents to do just that. “I’m having to articulate all the time … that there are a million people in the East Bay, [and] that’s enough of a market to call that a different market.” He spoke gravely. “If this concept isn’t embraced, then New Parish can’t succeed.”

Gallagher cited the example of a French band he scheduled to play Vitus this spring: “If they’re weighing it from abroad, they’re gonna want to play in the City. They’re from France; they want to see San Francisco. So I know I’m gonna have to lock them in now because when [San Francisco bookers] find out they’re gonna play an Oakland show, they’re going to give the band lip about [radius clauses].”

But big clubs and show presenters — the ones who benefit the most from radius clauses — argue that they’re less about predation than pragmatism. To that end, they’re usually negotiable, explained Jodi Goodman, Northern California president of Live Nation, a large booking agency. “The fact of the matter is: Artists, agents and managers understand a market pretty well, and know where the sensitivities are, and what discussions to have if they themselves have an agenda that is counter to a radius clause,” Goodman explained in a recent email. She added that a booker might reconsider those rules in the case of an artist who is big enough to sell out several venues in the same area without oversaturating his market. Take, for example, Paul Simon or Wilco, who both toured the Bay Area in recent years, performing in San Francisco, Oakland, and San Jose.

There also isn’t a monolithic bloc of Oakland club owners opposed to radius clauses. As Larry Trujillo, who books and co-owns The Uptown in Oakland, explained it, it’s in everyone’s best interest to keep supply and demand apace. “Basically, it all comes down to the size of the act, and to the relationships you have with the acts and other clubs,” he explained. “If you’re getting somebody big and putting down a big guarantee” — that is, paying them a lot — “you definitely don’t want them playing in SF three days later, and vice-versa.”

If a traveling act is planning to play a similarly sized venue in San Francisco, Trujillo said he knows it’s best to wait for the band’s next tour, both out of respect for his colleagues and concern for his bottom line. “That’s how all the clubs survive,” he said. “I’ve been doing this for 25 years, and after a while you get to know [other bookers]. We’re not out to screw each other.” In other words, such clauses can be a way of sharing risk.

However, the Uptown, a smaller venue, doesn’t compete as often with San Francisco clubs for well-known acts as do venues like The New Parish. That club’s owner, O’Connor, said that even when he’s not sidelined by radius clauses, he’s often left hanging until the last minute, waiting to see if a San Francisco show (or spate of shows) sells out before he books the band at The New Parish. Such was the case with the Portland electronic band Starfucker, which recently played The New Parish, Great American Music Hall, and The Independent. “I had to be the little bitch and wait,” he said. “It’s a dope show, they’re a hot band, and it looks good on my calendar, but it’s not gonna fucking crush.”

Dana Smith, who booked Starfucker at Great American, corroborated O’Connor’s story, saying that it was only after the San Francisco shows sold out that an Oakland date was added.

Given all this, East Bay venues have few avenues to try to play the system in their favor. Yoshi’s was actually one of the first Bay Area venues to buck the trend, declaring boldly, when it opened its San Francisco location in 2008, that it would contract certain artists to “split a run” at the two clubs. In other words, possibly the best — and only current — way for Oakland club owners to get around restrictive radius clauses is to open a San Francisco venue, too. That way, traveling bands get to play in the bigger city, while still having a chance to reach audiences in the East Bay.

Under the Yoshi’s system, a performer of the stature of Chris Botti or McCoy Tyner, who would have done a full five nights at the Jack London Square club, in the old days, might now do two nights in Oakland, followed by three nights in San Francisco. The whole strategy hinged on the somewhat heretical idea that Oakland and San Francisco could actually be treated as two distinct markets — that tourists in the Fillmore wouldn’t necessarily cross the bridge to catch a show in Oakland, nor would their counterparts in Oakland, Richmond, Berkeley, or Alameda have much interest in making a trek the other way. When the club first announced its plans, audiences, skeptics, and music industry gadflies immediately cried foul.

In spite of all the distrust, Yoshi’s seemed to have a viable business model — sort of. Former Yoshi’s SF Artistic Director Jason Olaine, who now works for Jazz at Lincoln Center, said that he had to treat the double-booking methodology as an ongoing experiment. “It’s been tinkered with over time,” he said. “One week in San Francisco followed by another week in Oakland isn’t gonna work for a jazz artist, unless it’s Wynton [Marsalis], Diana Krall, Botti, or Herbie Hancock — a pop jazz artist who can pull those kinds of numbers.” He continued: “The last big run we did was P-Funk, and that would have worked, except we did one show too many. So we overshot a little.”

He added that over time, he narrowed the double-booking to two nights per venue, and often tried to bill them as different experiences: Maybe he’d have Japanese pianist Hiromi play with an acoustic trio in Oakland and an electric band in San Francisco, for example. As Yoshi’s kept refining the format, it became a good way to optimize revenue.

Other clubs followed suit. The New Parish, which opened in 2010, makes a point of sharing lineups with its sister venue, Brick & Mortar Music Hall, which launched the following year in San Francisco’s Mission District. Live Nation and Another Planet have tried this practice, too, albeit sparingly. The current calendar for Another Planet shows that Wilco will play a show at the Fox Theater in Oakland on January 31 and a show at Davis’ Mondavi Center the following night. Then there’s Paul Simon, who can pretty much sell out any stage he chooses, and therefore has a lot of latitude when signing contracts; when he toured the Bay Area last spring, he played at the Fillmore, The Fox, and Davies Symphony Hall.

But O’Connor has found that in several years of hammering home the argument against radius clauses, he’s been one of the few voices of dissent. According to Gallagher, the vast majority of clubs — “even little punk-rock hole-in-the-wall venues” — in San Francisco still employ radius-clause language in their contracts. Even the clubs that double-book usually still hew to the old contract language, be it a rule of ninety days, ninety miles for an A-list act (i.e., when there’s a lot of money on the line), sixty days, sixty miles for someone slightly lesser-known, or thirty days, thirty miles, etc. The terms can be made flexible if the artist agrees to play for less money, thereby minimizing risk to the venue operator. But the anti-competitive sentiment remains, and, in O’Connor and Gallagher’s estimation, it now has less justification.

Yet even Yoshi’s hasn’t abandoned radius clauses. It will book artists in both Oakland and San Francisco, so long as the performers agree not to play at another local jazz venue for ninety days.

At its core, the entire argument about radius clauses hinges on whether San Francisco and Oakland are, in fact, separate markets — an argument which is far from resolved among industry heads.

Proponents of radius clauses argue that despite all the development in Oakland in recent years, it’s still tough to play within the ninety-mile radius without oversaturating your market. According to Scott of Another Planet, the prevailing rule of thumb is the more popular an act is, the more likely people will be willing to travel to see it. In other words, people are much more apt to hop on BART or cross the Bay Bridge for Lady Gaga than they are for an obscure indie band.

Rick Mueller, who books The Warfield, The Regency Ballroom, and, on occasion, the Oracle Arena for local music presenter Goldenvoice, said the rules are sometimes murky — a global headliner like Madonna or U2 would only hit one Bay Area venue, whereas someone with slightly less draw, like Paul Simon, could either choose to do one large venue (like the Greek) or divide his audience between three rooms, if he wants to provide his fans with a few different settings.

But it’s a risk either way, radius-clause advocates say: Scott’s general belief is that if an artist splits a run between the East Bay and San Francisco, he or she can expect about a 20-percent increase in sales. “So say an artist can expect to sell five hundred tickets on one play in a market,” he explained. “If they play in Oakland and San Francisco, maybe we can get a 20-percent delta, or six hundred tickets. So they might do four hundred seats in San Francisco and two hundred in the East Bay.” So while you can pick up a limited number of audience members by playing in their neighborhoods, no act can double its fanbase just by moving across the bay, he said. In other words, you simply can’t create consumers out of thin air. “It’s all supply and demand,” Scott said.

But opponents of radius clauses argue that artists may actually be better off playing multiple venues and treating the Bay Area as a collection of microscenes. A fitting example is Living Legends rapper The Grouch, who fared better splitting his 2010 “Grouch Stole Christmas Tour” between The New Parish in Oakland and The Independent in San Francisco than he did playing exclusively at the Fillmore the following year. According to O’Connor, he sold out both the Oakland and San Francisco clubs in 2010, with a cumulative audience of about nine hundred; at The Fillmore, he only sold four hundred tickets. Or take Starfucker, whose booker, Avery McTaggart, said is having increasing success booking in Oakland and San Francisco. “A band like Starfucker, which has historically played midsized venues in San Francisco, can now sell out in Oakland,” he said confidently.

In fact, O’Connor argues that many artists have distinct fanbases on different sides of the bay. Take electronic band Little Dragon, which has its own cult of adoration in San Francisco, but also appeals to the multiracial house scene in Oakland. “That whole People Party scene definitely loves Little Dragon,” he argued. Starfucker, too, evidently has its own draw in Oakland; another example of a band cleverly appealing to different niches might be the Brooklyn-based Afrobeat band Zongo Junction, which a few weeks ago played one show at Slim’s to a crowd of twentysomething hipster types and another the following week for Ashkenaz’ older-skewing, world-music-oriented clientele.

O’Connor and Gallagher consider the success of these bands’ approaches as evidence that the Bay Area actually comprises several discrete markets. To them, the logic is simple: excepting the very biggest acts, people don’t travel far for live music, so it behooves most artists to work on a neighborhood-by-neighborhood basis. Put another way, you’re more likely to go check out a show if you can ride your bike there. And furthermore, O’Connor argues that any area the size of Oakland — with its own downtown, its own professional sports teams, and a large university nearby — deserves to be its own market.

Many venues also promote their shows exclusively on one side of the bay — an indication that even they see the bridge as a big enough geographic barrier for audiences not to cross over. “It became obvious to me that these places were two different markets about fifteen years ago,” O’Connor said. “There’s been more musicians living in Oakland than San Francisco for a long time. There’s a bigger metal scene, and a bigger hip-hop scene.”

For that matter, he maintained, the only thing that Oakland doesn’t have going for it is name recognition. Because bookers and agents consistently overlook it, mid-to-large-size venues like Vitus and The New Parish face much bigger challenges than their counterparts across the bay.

Ultimately, O’Connor said that if New York promoters can make sharp delineations between Brooklyn and Manhattan, then the same can definitely be said of Oakland and San Francisco — and that may actually be a conservative analogy, since Brooklyn and Manhattan are, in many senses, closer together than their West Coast counterparts. “Brooklyn is literally ten minutes away from Manhattan — possibly eight minutes,” O’Connor argued. “That’s a bike ride, a $1.50 subway token.

“Whereas Oakland and Berkeley are half an hour from San Francisco in a car, or $6 by public transit, and you can’t bike,” he continued. “That means if you’re in the East Bay, you want to stay in the East Bay.”

And with transbay BART service ending at around midnight, it’s hard for folks from the East Bay to get to and from a show in San Francisco without having to drive (and therefore stay sober). As Gallagher argued, “until BART opens up, it’s not the same market.”

But at the end of the day, the truth about whether Oakland and San Francisco are, in fact, the same market is, of course, probably somewhere between these two poles. (Trujillo, in fact, said he sometimes likes to think of the Bay Area as “one-and-a-half markets.)

But here’s the thing: Because radius clauses have been industry standard for so long, there’s no viable means of knowing the truth. As long as such limits on competition exist, no one has the chance to figure out by trial and error where exactly the sweet spot is between under- and oversaturation.

Which is a shame for Oakland. In the most fatalistic view, the city can invest all it wants in infrastructure, but it will ultimately always be relegated to second-best by virtue of the system in which it exists. And though there are several ways East Bay venues could overthrow the radius-clause standard, each has its own challenges.

First, club owners could sue. O’Connor has threatened to do just that. He said in a recent interview that he’s considered launching a class-action lawsuit to demand that Berkeley and Oakland be designated as separate markets. But San Francisco attorney Joshua Koltun, who specializes in anti-trust and media law, warned that unfortunately, it would be pretty hard to litigate — the onus would be on O’Connor to prove that San Francisco clubs weren’t just using contracts to protect themselves, but that they were also acting collusively to shut Oakland out.

Koltun offered the analogy of automobile manufacturers who often use similar language when contracting with retailers. “They’ll say, ‘We’ll let you open a dealership for our project, but you can only sell within a restricted radius,” he said.

The Lollapalooza case in Illinois warranted investigation, Koltun continued, because it involved an entity with a lot of power trying to create an unreasonable restriction. In contrast, though, it would be difficult to prove that San Francisco clubs are conspiring to undermine their Oakland counterparts.

Another option is for artists and their booking agents to take it upon themselves not to sign contracts with radius clauses. But even that seems unlikely, Gallagher said. He’s actually had some luck convincing acts to skip San Francisco entirely in favor of Oakland — but, ultimately, it’s tough to persuade an artist who’s never been to the area to bypass the best-known city in the region, or to convince someone you’re never met not to sign a contract.

Moreover, he said, many bands simply don’t read all the fine print before signing, or their management company deals with the paperwork on their behalf. And in a difficult financial climate in an industry where many bands shoulder the burden of filling every venue they play — which is, indeed, the case for most small-to-midlevel music acts in the Bay Area — asking artists to fight the system would mean asking them to take a significant risk. The truth is, all but the biggest bands are generally at the mercy of venues, and inspiring any kind of industry-wide backlash against radius clauses would be far from easy.

Perhaps the most likely solution would be to encourage more venues to adopt the Yoshi’s and New Parish model, or some variation thereof — that is, to co-present shows on both sides of the bay and in such a way that neither venue is at financial risk. But that would require venues to have the capital to open up a new sister club — again, not easy in this climate.

There’s a fourth solution, too, or maybe it’s part of another solution: Wait for Oakland’s nightlife scene to coalesce into something with real influence and appeal within the industry. In fact, the prevailing sentiment appears to be that Oakland’s moment just hasn’t come yet. “I’m really excited about what’s happening in Oakland,” said Scott of Another Planet. “It just takes time.”

McTaggart, Starfucker’s booker, said Oakland’s mystique is beginning to build within booking-agent circles, largely because of all the new venues. “It used to be, if bands were playing in the East Bay, they were playing at the Greek,” he said. “But now the Fox is attracting a lot of bands, and so is The New Parish.”

Still, it may take a while before music industry types are willing to bank on an emerging scene. Furthermore, Oakland’s downtown has had the backward fortune of beginning to bloom at a time when the music industry started to struggle nationally; Scott believes that as the wider market picks up, Oakland may be primed to absorb that new business.

And even now, there are some silver linings. For one thing, radius clauses have had the unintended consequence of spawning a thriving warehouse scene, as many bands have been forced by contracts to play secret shows and underground venues. Ross Peacock of the band Mwahaha says he occasionally circumvents the rule by playing warehouse shows or house parties, which aren’t advertised and can serve to promote a larger show at a legit venue. “I had one band tell their management they were playing as a backing band for a birthday party, and then they came [to Vitus] and played an unadvertised show,” Gallagher recalled.

And just because East Bay clubs can’t always get the big names, venues like The New Parish and Vitus are building their reputations on booking riskier, edgier, more up-and-coming acts — which can potentially pay off. For his part, Gallagher, ever the optimist, believes Oakland is on its way to becoming the kind of place bands prefer to play, based on quality of experience. He recalled a national touring band that came through town a few years ago and opted to skip the City altogether in favor of downtown hole-in-the-wall Cafe Van Kleef. The cover was minimal, the drinks were stiff, and the house was packed. “It’s just this little neighborhood bar, but there weren’t any rude bouncers, they weren’t trying to just get you in the door and take your money. People were actually dancing, instead of standing against the wall.”

Later, Gallagher said, the band members told him it was the best night of their tour.