Last month, Oakland Interim Police Chief Sean Whent told the city council that Oakland’s gunshot detection system wasn’t a high priority, and that the police department might be better off spending the $264,000 that ShotSpotter costs the city each year on other technologies or programs. OPD spokesman Frank Bonifacio told the San Francisco Chronicle that the department “has recognized that other tools and technologies may be more valuable at this time, such as the police helicopter or air support.” OPD officials also maintained that the department has trouble responding to the automated alerts of gunfire because of staffing shortages — the very reason why Detroit decided to not sign a contract with ShotSpotter in 2012. The comments by Whent and OPD officials, along with the Chronicle article, sparked a flurry of public statements from Oakland politicians in strong support of keeping ShotSpotter’s gunshot sensors in the city.

“Recently, we learned — through the news media — that your Administration is considering terminating the city of Oakland’s ShotSpotter services,” councilmembers Rebecca Kaplan and Larry Reid wrote in a public letter to Mayor Jean Quan on March 24. “[W]e believe that eliminating ShotSpotter would be a grave mistake.” Quan quickly issued her own statements in support of keeping ShotSpotter.

Behind the scenes, ShotSpotter has been busy pressing its case with city officials in recent months, not just to keep the existing system, but also to expand it. The problem, however, is that ShotSpotter appears to be in violation of Oakland’s lobbying rules; the Newark, California-based company is not registered as a lobbyist with the city even though it routinely lobbies members of the city council, the mayor, and the city’s administration, including high-ranking members of the police department, according to city records.

Oakland’s Lobbyist Registration Act, passed in 2002 and amended in 2006, requires companies that seek to do business with the city to register as a lobbyist with the city clerk, and to file quarterly reports, documenting which issues they have contacted Oakland officials about.

“Oakland has strong lobbyist registration and reporting requirements that are intended to let the public clearly see what their public officials are doing and who they’re meeting with,” said Kathay Feng, the director of the good-government group California Common Cause.

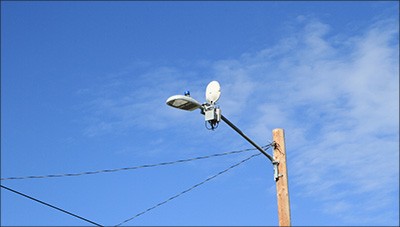

ShotSpotter’s technology involves setting up microphones on lampposts and utility poles around Oakland. The microphones, which are linked via a wireless network, are designed to pinpoint the location of any gunshot and transmit an alert to police with the date, time, location, and a recording of the noise that triggered the alert. The company touts its technology as being more effective than witness reports. Earlier this month, ShotSpotter released a study claiming that witnesses reported less than 13 percent of all gunfire in Oakland neighborhoods equipped with the company’s technology. According to the company’s data, its microphones detected 8,769 gunfire incidents in Oakland in 2012 and 2013, but residents reported only 1,136 such incidents to police. ShotSpotter is used by more than sixty cities across the country, including Washington, DC; Milwaukee; and San Francisco.

But Oakland city records show that ShotSpotter was pressing members of the city council to expand its system at exactly the same time Whent and his command staff were re-thinking the efficacy of the technology. Joe Hawkins, senior vice president of ShotSpotter, wrote to Councilmember Dan Kalb on March 13 inviting Kalb to an “informal meeting” with ShotSpotter CEO Ralph Clark. While making his pitch, Hawkins referred to mutual friends and noted that he and Clark are both Oakland residents.

“I haven’t met with anyone,” said Kalb when we asked him about ShotSpotter. “Generally, I’m supportive of ShotSpotter. But if somebody’s violating the existing requirements, then by all means that should be fixed.” Kalb added that he doesn’t know if the company has talked with other councilmembers.

ShotSpotter’s vice president of marketing Lydia Barrett wrote to councilmembers Noel Gallo, Kalb, and Kaplan on March 7 requesting that they schedule a presentation for the company at a public safety committee meeting. “With any current discussion on ShotSpotter information, we’d like to make sure we’ve got the opportunity to present accurate and timely information to the Council and committee,” wrote Barrett.

According to another email sent to Kaplan by ShotSpotter’s Hawkins and Clark, the company’s executives met at least twice with the councilmember and her staff, with the last meeting taking place on March 20. They discussed expanding the system to Maxwell Park, Cleveland Heights, and downtown Oakland at a cost of $146,600. Six days later, ShotSpotter submitted a detailed proposal to Kaplan and OPD. Kaplan’s spokesperson Jason Overman declined to comment for this report, and referred questions to the Oakland Public Ethics Commission.

Council President Pat Kernighan said she hasn’t met with ShotSpotter representatives, but she told us that she noticed the company’s executives as they were making in-person visits to City Hall in early April.

ShotSpotter’s concerted pressure on Oakland officials last month paid off. According to Oakland police spokesperson Johnna Watson, Whent met with a ShotSpotter representative on March 26, two days after Kaplan and Reid sent their letter to Quan and the news media. Watson said Whent’s meeting with the ShotSpotter representatives was productive. “They discussed the value in continuing to utilize ShotSpotter as a tool in crime fighting and agreed that a continued partnership is our goal,” Watson said. After the meeting, OPD officials submitted a request for continued funding for ShotSpotter’s contract as part of their mid-cycle budget request.

After reviewing the emails and Oakland’s lobbying rules, Feng said ShotSpotter did not appear to be following city regulations. “When a company that does business with the city, and is lobbying for an expansion of a contract, fails to register as a lobbyist, they are circumventing the laws that Oakland has put in place,” she said.

Feng added that ShotSpotter’s pressure on elected officials — in direct opposition to the stance Whent had originally taken — highlighted a core reason why lobbying rules exist. “One of the things that we’re always concerned about is allowing the people with the greatest expertise to decide public policy without the influence of special interests,” she said. “In this case, if the police chief is saying they want to spend money on different programs, especially when there’s a company that stands to benefit, the public has the right to know whether the company is trying to influence decisions and exerting pressure.”

The penalties for failing to register and report on lobbying activities can include fines of up to $1,000 for each complaint sustained. If a person has knowingly or willfully violated the Lobbying Act, he or she can be found guilty of a misdemeanor and barred from lobbying for one year.

According to public records, ShotSpotter is aware of government lobbying laws. For example, the company has registered as a lobbyist employer with the US government. According to Congressional disclosure records, ShotSpotter spent more than $1 million since 2004 to lobby the House, Senate, the departments of Justice and Homeland Security, and the military. According to federal procurement records, ShotSpotter has been awarded approximately $2.4 million in contracts by the Navy, FBI, and Air Force over the past decade. ShotSpotter’s federal lobbying efforts also help the company to secure grant funding through the US Department of Justice that cities can apply for in order to purchase the company’s gunshot detection system.

ShotSpotter representatives did not respond to phone call and email requests for comment for this report.

As for Quan, she appears to have had few meetings with ShotSpotter. Her spokesperson Sean Maher said that right around the time Quan became mayor she was in a meeting with ShotSpotter to try and lower the cost of the program. Maher also said Quan and her staff had not met with ShotSpotter representatives during the time when Whent and top police officials were thinking about killing the contract. “No one in the Mayor’s office, including Mayor Quan herself, has been contacted by ShotSpotter since March 3, 2014,” Maher wrote in an email.

The Oakland Public Ethics Commission, which is charged with tracking and enforcing the city’s lobbying rules, has a staff of only two people and relies on interns for posting data online. Twenty-four lobbyists have registered with the commission in 2014. The group includes financial companies, landlord associations, and technology vendors. The Public Ethics Commission’s funding comes from the city’s general budget. Oakland does not levy a lobbyist registration fee, as is standard practice in other jurisdictions like San Francisco, where lobbyists must pay $500 before seeking contact with lawmakers and city staffers.

Correction: The original version of the story erroneously stated that the City of Detroit decided to sever its contract with ShotSpotter in 2012. In fact, the city decided that year not to sign a contract with the company.