The City of Oakland and Alameda County have agreed to pay $1.025 million in damages and legal fees to demonstrators arrested on November 5, 2010 in Eastlake during protests over ex-BART cop Johannes Mehserle’s sentencing for the killing of Oscar Grant. Evidence in the case showed that the Oakland Police Department violated a 2004 court order concerning the handling of large numbers of protesters. None of the 152 people arrested that night by Oakland police were charged with criminal offenses related to the march, and the sheer volume of arrestees overwhelmed Alameda County sheriff’s deputies, resulting in dozens of people being held on buses while handcuffed for up to six hours.

The settlement of the case Spalding et al v. City of Oakland, which was announced this week by the National Lawyers Guild, was the first of three class action lawsuits resulting from OPD’s reaction to protests from 2010 through 2012 linked to the Oscar Grant case and Occupy Oakland. The two other cases, Campbell et al vs. Oakland and Angell et al vs. City of Oakland, allege the use of excessive force and unlawful mass arrests by OPD during demonstrations on October 25, 2011, November 2, 2011, and January 28, 2012. The January 28 incident resulted in police arresting more than four hundred people outside the Downtown Oakland YMCA. A proposed settlement in the Campbell lawsuit is scheduled to be taken up by the Oakland City Council on July 2.

The settlement in the Spalding case, which is named for Dan Spalding, a National Lawyers Guild legal observer who was arrested by police during the November 5, 2010 demonstration, has received tentative approval from federal Judge Thelton Henderson. The settlement is expected to become final by September after protesters who were arrested during that demonstration approve it.

The Spalding settlement also reaffirms OPD’s crowd-control policy, which was the result of a 2004 court order that restricted the use of less-than-lethal weaponry, required OPD to issue citations for misdemeanor arrests during protests, and forbade mass arrests for non-criminal offenses such as blocking traffic or marching without a permit. Policies for the Alameda County Sheriff’s handling of misdemeanor mass arrests were also crafted during the settlement process.

The settlement concluded that OPD’s conduct on November 5, 2010 violated the court-ordered crowd-control policy, which was established after a violent police response to a 2003 antiwar demonstration at the Port of Oakland. “The overall idea of the policy is for the police to use the minimum level of force as opposed to the maximum,” said Rachel Lederman, an attorney with the National Lawyers Guild. Characterizing mass arrests and lengthy detention of peaceful demonstrators as “pre-emptive, precharging punishments by the police,” Lederman claimed that the November 5, 2010 mass arrest had “a really chilling effect on free speech in Oakland.”

The arrests were the end result of a nighttime march that began at Frank Ogawa Plaza. Hundreds of people began gathering there that afternoon after Los Angeles County Judge Robert Perry overturned a gun enhancement charge on Mehserle’s involuntary manslaughter conviction. Judge Perry’s decision reduced Mehserle’s maximum possible prison term from fourteen years to two years. The former transit cop then served eleven months in protective custody in Los Angeles County jail and was released in June 2011.

Mehserle’s reduced sentence spurred outrage from many residents of the Bay Area, who spent the afternoon of November 5 demonstrating at 14th Street and Broadway in downtown Oakland as neighborhood businesses, offices, and banks boarded up windows and told employees to leave work early to avoid potential unrest. A group of three hundred marchers left Ogawa Plaza that evening with the intent of going to the Fruitvale BART station, where Grant had been shot to death while lying facedown on the ground.

Hundreds of Oakland police in riot gear and cops from departments throughout the East Bay, the Peninsula, and Marin and Monterey counties turned out to confront the marchers and briefly surrounded them on 12th Avenue behind Laney College. The marchers escaped after some demonstrators tore down cyclone fencing that guarded a construction site for the now-completed Measure DD repair project at the western end of Lake Merritt. After continuing up International Boulevard for several blocks — where at least one store window was broken — the demonstrators were diverted by police into the Eastlake neighborhood. Police eventually cornered 152 people at 6th Avenue and 17th Street.

Excerpts from OPD’s radio traffic from that night reveal that police intended to surround and arrest anyone who engaged in a march — without declaring unlawful assembly or following the crowd-control policy.

“The first opportunity you can, set up a surround to arrest. We’d like to employ that,” Deputy Chief Eric Breshears said to Captain David Downing in a transmission obtained by the National Lawyers Guild.

“Do we want to make announcements for unlawful assembly or they’re already just under arrest?” Downing asked Breshears.

“Affirm. Based on their activity over here, the vandalism that’s occurred, affirm that it’s unlawful assembly. You are to arrest everybody that’s within that perimeter,” Breshears replied.

Police maintained the perimeter for an hour, and then made an announcement that they would allow news media members with credentials to leave. An officer then announced: “This has been declared a crime scene and you are all under arrest.”

Lederman said Breshears’ actions violated OPD’s crowd-control policy. “They have to have a basis to declare unlawful assembly aside from isolated acts by a few individuals,” Lederman said. “Then, they have to audibly declare an unlawful assembly and give people a chance to disperse, but Deputy Chief Breshears gave this order to declare the area a crime scene” and arrest everybody.

The National Lawyers Guild believes the arrest plan was preconceived by Breshears, then-Assistant Police Chief Howard Jordan, and then-Police Chief Anthony Batts. At his deposition, Downing testified that he was prepared to give an unlawful assembly announcement and provide an opportunity for dispersal, and did not know why Breshears deviated from standard procedure.

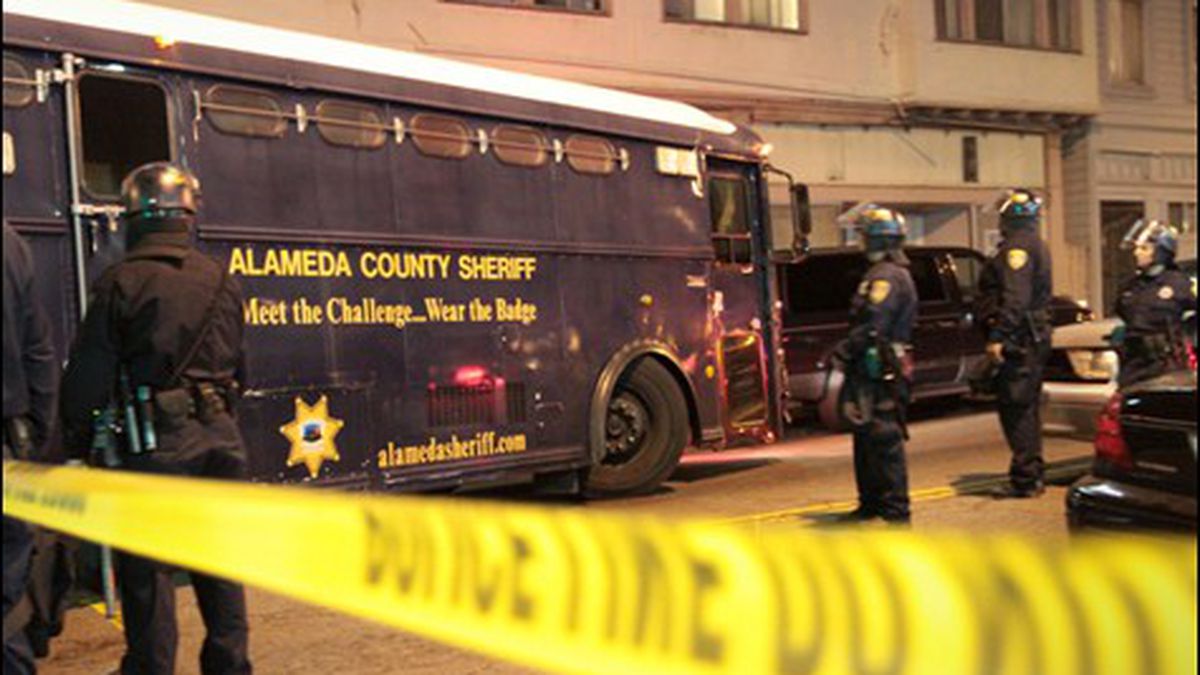

Alameda County Sheriff’s Office buses arrived at the scene to transport the 152 arrestees to jail. Because of the sheer volume of people, sheriff’s deputies at North County Jail in Oakland kept many of the detainees on buses for up to six hours while handcuffed. As a result, numerous people urinated on themselves while waiting to be processed. Female detainees were also required to give urine samples for mandatory pregnancy tests.

Katie Loncke, a plaintiff in the Spalding suit, recalled being held in a temporary holding cell with fifteen other women, without furniture, heat, or food. “No food was provided for more than twelve hours after our initial detention,” Loncke said. “There was no room to lie down. I sat up against a wall for the entire night.”

Aside from two people held for criminal charges unrelated to the march, the other 150 protesters were released within 24 hours without any charge related to the demonstration.

Anyone arrested during the march on the night of November 5th, 2010 may be entitled to $4,400 in compensation and an order of exoneration purging his or her arrest records. Each potential claimant must fill out paperwork from the National Lawyers Guild and return it by August 5 to benefit from the settlement.