In 2008, Devon Blood watched himself getting shot for the first time. He was popped in the head on July 12, 2006. The .22 caliber bullet entered just below his right ear, and lodged in his skull.

A video camera captured it all: Four armed men broke into a warehouse where Blood lay in bed with his girlfriend, Tammy Wartvee. Most likely it was a mix-up — the guys probably thought they were burglarizing the pot club next door in the same building. They had come the night before, plundered a few bags of marijuana, and driven off with their loot. But no one had told Blood or Wartvee about that incident, much less warned them that the suspects were still at large.

Devon Blood was an accomplished tattooer and artist before the shooting. Credits: Devon Blood

A tattoo by Devon Blood. Credits: Devon Blood

A tattoo by Devon Blood. Credits: Devon Blood

Devon’s mother Linda kisses her son during his coma. Credits: Mia Blood

Blood concluded that he would have to retrain himself to write and tattoo with his left hand. Credits: Linda Blood

Blood discusses some of the work at a recent show at the Old Crow Tattoo Gallery. Credits: Hali McGrath

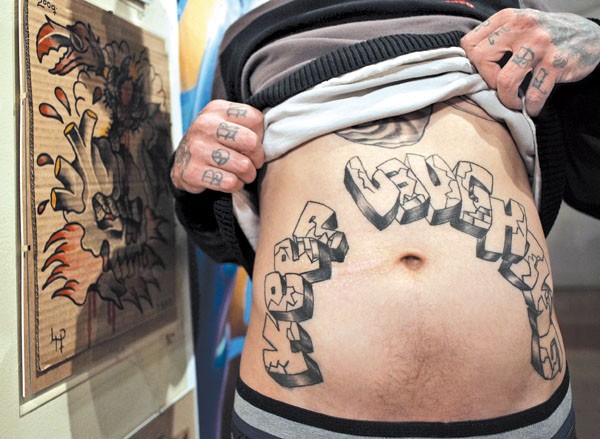

Blood shows off the “Keep Laughing” tattoo a friend added to the area above his scar. Credits: Hali McGrath

What’s frustrating is that it should have been an easy crime to solve. The pot club had a surveillance camera, which caught footage of both the July 11 caper and Blood’s shooting on July 12. All the details were clear as day. “You could see the guys pull up in the getaway car, break in, score a bunch of bags of marijuana, then come back the next night,” Blood recalled. “Same car, same guys, leaving with nothing. The whole time on the videos you could see the rear license plate of the car and you could see what the guys looked like.” What happened next gets a little more hazy.

Blood was still conscious when he got to Highland Hospital, shortly after 1 a.m. He could raise and lower his limbs on command, but when the doctors took a scan of his head they found a black hole filled with a bunch of shrapnel, and a rapidly swelling brain. Blood needed a major crainiectomy. So that night the doctors put him in a drug-induced coma, cut his head open, removed his right skull cap, and sewed it inside his stomach to preserve it in an environment in which the bone and tissue would survive until it could be returned to his head months later — if he lived that long. They swaddled his head in bandages and moved him to a hospital bed beneath a sign that read: “Do not turn patient on his right-hand side.”

In the Intensive Care Unit, Blood was hooked up to a respirator, heart monitor, and blood pressure monitor. He had tubes running from his nose and oxygen sensors on his fingers. At one point, things got pretty bleak. The doctors performed tests on Blood a couple times a day by holding his eyes open. “One would stay looking one way, the other would fall,” said Blood’s close friend and fellow tattooer, Matt Howse. “They would say, ‘That’s a bad sign.'”

Before the shooting, Devon Blood was one of the most prominent tattooers in Oakland and a ruthless skateboarder to boot. He was twenty-six years old, thin but tough-looking, and had scads of friends in the local tattoo scene. He had a pierced septum and enough tattoos to make his body resemble a Neo-Expressionist painting. An ink butterfly spreads across his throat and a small blue diamond gleamed below his right eye. His left and right knuckles bore the words “Born Rebel.”

Now it wasn’t clear if he’d ever wake up, or if he’d live the rest of his life in a quasi-vegetative state. Because so many Oakland shootings are gang-related, raising fears that someone might come back to finish the job, Blood’s friends and family had to furnish code names just to enter his room and keep watch. Blood’s mother, Linda, enlisted friends to pray over her son’s bed. Howse brought a tattoo machine to the ICU, placed it in Blood’s limp right hand, and turned it on.

Blood is Linda’s maiden name, and it runs thick in her family. “My husband changed his name consistently,” she said, “but my kids all have the Blood name.” Linda had an on-again, off-again relationship with Devon’s father, a rock musician who left the house for good in 1984. Linda had just given birth to twins, one of whom died of Sudden Infant Death Syndrome that March. The loss put a strain on their relationship, and dad ultimately decamped to pursue his music career in Los Angeles. “He dug out on all the kids,” Linda said. “He didn’t pay child support. When the district attorney finally found him, he said, ‘None of the kids are mine.’ The poor kids had to have blood tests.”

Linda made do the best she could as a hair stylist and doll maker. She raised the kids in a small house in Pacifica, encouraged them to play sports, and made them attend church each Sunday. She kept a full roster of hair clients and sold dolls at San Francisco art and wine festivals. Devon spent his early school years at Coastside Christian Center, where he had to arrive every day in a maroon vest and corduroys. The principal doubled as a pastor in the local church, and Devon remembers him having a sweet tooth for corporal punishment. “He had a paddle framed on his wall like a shadow box,” Devon said. “It had a peace dove painted on it. If you were really bad, he would paddle you with it.”

And Devon got paddled, even though Linda remembers him as the type of kid who almost never got into scrapes. Once he came to school with holes in his corduroys and got sent to the principal’s office. It turned out the principal had a secret cache of paddles in a drawer. “He pulled out a paddle with holes in it, so it let the wind through,” Devon said. Another time, Devon got in trouble for throwing bark at another kid on the playground. This time, the paddle had big wooden pegs. Devon was happy when, during first grade, a fire burned the academy to the ground. He got transferred to a public school.

Over time, Devon learned to be rugged and independent. He rode his bike all around town, kept sketch pads full of drawings and paintings, and skateboarded at all the hot spots — most notably the Embarcadero, Fort Miley, and Union Square in San Francisco. He could do just about everything: front-side heel flips, 360 kick flips, half pipes, no complies, and back-side ollies. He was small and agile. “I didn’t hit puberty until I was eighteen,” he said. “There are pictures of me tattooing with no facial hair.

In the seventh grade, Devon begged his mother for a tattoo. “She said that when she and her friends were seventeen they used to go to the art store, buy a needle and thread, and give themselves tattoos,” he remembered. Linda capitulated. She took a regular sewing needle, wrapped thread around it to soak up the ink and ensure it would only go to a certain depth, and wrote Devon’s name on his leg, with clovers. In the business that’s called a stick-and-poke. It’s perhaps the most primitive and unsanitary way to ink up the human body, but it works. Devon decided to try the art on all his friends, much to their parent’s dismay. One friend’s tattoo got infected. “It’s not clean. Too much cross-contamination going on,” said Devon, who eschews the stick-and-poke method today. But even then, he saw the makings of a new enterprise.

In the mid-nineties Linda moved the family from Pacifica to Fremont. They rented a house in the Niles district, and after it was foreclosed on, they found a large Victorian on Decoto Road. That was Linda’s dream house, remembers Devon’s friend Jimmy Tobias. It lay on a full acre of land, had multiple floors, bedrooms for all the kids, and ample space for everyone to run around. How they lost it remains a matter of debate.

At the time, Devon was fully ensconced in the local skateboarding scene. He attended a secondary school and ran with a pretty mixed group of kids. “It had a smoking section and a day care, just to give you an idea,” Devon recalled. Not to mention that each of his nine siblings had their own friends. People were constantly coming and going from the house on Decoto Road, Devon said. The presence of so many punk teenagers gave the Fremont cops a reason to be suspicious. Not to mention that Linda had a hard time turning people down when they needed a place to stay. She let Devon’s friends Aaron and Joe shack up in the basement, even though Joe was on probation — supposedly for carjacking in another state. “He was wanted by the FBI,” said Linda. “He got a driver’s license and used my home address.”

Devon doesn’t recall those details, but says that overcrowding and constant loitering at the Decoto spot made it look as though the Bloods were running a large drug operation. Then, one day, a bunch of cops pulled up to the house, drew their guns, and kicked the doors in. It turned out Joe had a warrant out for his arrest, Linda said. “The sheriff of Alameda County said, ‘You have to leave the property until we find this guy.'” So they packed up and moved to an “extended stay” motel with one bedroom and a kitchenette, while Linda waited for a new apartment to open up. Devon opted to couch-surf and stay in his car.

“It made me cry,” Devon recalled. “It was my mom, my step dad, and one of my sisters on the floor. And everybody else on the bed. It was like a sardine can. I was like, ‘You know what? I’ll just sleep in my car. It’s fine.'”

For the next few years, Devon’s housing situation was shaky. In tenth grade he got a job at a local sandwich shop and rented an apartment with some friends. When that disintegrated, he tried couchsurfing. He lived in his car intermittently. Cops would knock on the car window at 3 or 4 a.m. and tell him to leave.

But all the while, his friends say, Devon was on his way to becoming one of the most respected tattooers in the East Bay. Devon distinguishes between a “tattoo artist,” someone who merely applies art to skin, and a “tattooer,” a tattoo artist who also makes his own supplies, tunes his machines, and imparts historical facts about tattooing. In high school, Devon started apprenticing with a man named Donnie Irish, who ran a fully licensed tattoo parlor out of his Fremont home. Under Irish’s wing, he graduated from the stick-and-poke method to operating a machine. He learned how to properly outline and shade stuff. At age nineteen he took a job tattooing at Industrial in Berkeley, which paved the way for another job at Sacred Tattoo — one of the better-known parlors in Oakland.

“He’s a fantastic artist,” said Petaluma tattooer Clayton James. “Tattooing is a very hard thing to do, and the profession is a lot more like a family than most other professions. It’s not just a job, it’s a lifestyle.”

When he wasn’t tattooing or skateboarding, Devon dabbled in other forms of art. He painted watercolors, designed skateboard decks, and made his own tattooing needles and built his own supplies. He used acrylics and oil paints to decorate pieces of cardboard or scavenged wood. For a while he lived across the street from a lumber yard, and he was constantly turning scraps into art. His paintings were grisly, said Alex Turan, a fellow skateboarder who lived with Devon in 2004. Inspired by old Santa Cruz skate decks and slasher film imagery, they featured lots of birds of prey or severed geisha heads, like the one tattooed on Devon’s neck. “You can see some of his girls from the past,” Turan said. “They’re still cutting their throats and stuff, but they’re pretty. “He’s not drawing girls anymore. Now it’s skulls. Now it’s about anguish.”

Howse concurs. “His art used to have elegance, now it’s bolder and more brutal,” he said. “It’s just bang, bang, bang.”

The night of July 11, 2006, Blood was staying with his girlfriend at a warehouse on 20th Avenue in East Oakland. Wartvee lived there with three other people, all punk musicians. The place had three regular bedrooms, and one bed in what was supposed to be the living room. It was a large, white, blocky building, wedged between a taqueria and a cannabis club. The windows were high-up and barred. The front door was guarded with an iron security gate. The whole area was zoned for industrial purposes, Blood said, but the landlord rented that space out to make extra money.

Some time after midnight, a white sedan pulled up and four teenagers jumped out. Blood says they were the same group of kids who had robbed the pot club next door just the night before. Who these kids were is still a matter of debate, since they were never apprehended. But they clearly came ready to score, and they were armed.

Blood was laying in bed with Wartvee when suddenly they heard a large thud, followed by the sound of wood and glass breaking. Unable to break through the metal security door in front, the burglars had opted to kick through a set of loading-dock doors near the side of the house. To do that, they stationed one guy below while the other three went across the street, sprinted up to the house, jumped up in the air, and kicked in the doors on the way down. The first guy caught them after they collided with the doors.

Within moments, the wood splintered and caved in. Blood and Wartvee panicked. “I was like, ‘There are people breaking in, get out the back window,'” Blood remembered. Wartvee reached for the window and found it all barred up. “There weren’t breaker bars, and it wouldn’t budge,” Blood said. “We were like sitting ducks.” Just then, he heard footsteps.

Blood threw himself against the bedroom door. “I was like, ‘Screw it.’ I didn’t want them to get in the room and kill us both.” He heard the burglars creep through the house and up to the bedroom. He felt someone’s weight on the other side of the door and heard the knob turn and stick. Then he heard a shot.

He was shot once, in the head. A .22 caliber bullet had gone straight through the door, behind his right ear, and into his skull. He collapsed, and the trigger man jimmied the door open a crack, just enough to start firing around the room. Within seconds the whole door and a blanket on the bed were riddled with bullet holes. “If I didn’t go down by the first shot,” said Blood, “I would have been killed by fire.”

Wartvee ducked and escaped gunfire. The four burglars fled the house with nothing, jumped in their getaway car, and sped away. Wartvee wrapped a towel around her knee and pressed it against her boyfriend’s head. When the ambulance arrived, Blood was surrounded by a pool of blood that spread several feet.

“When they found him …” Linda said, “they looked at him and said, ‘He’s dead, he’s gone.'”

Blood’s memory of the subsequent events is rosier than those of the friends who came to watch over him. He describes being stuck in a coma is tantamount to sleeping for a very long time. You cycle through dream after dream after dream, each one more detailed than the last. You hear people talking in the room and their conversations bleed into your psyche. Dark bleeds into light, shadows lengthen and recede, without your knowledge of any time passing. “When I woke up, I thought I’d only slept one night,” said Blood. “I was like, ‘Mom, what happened?'”

Actually, it didn’t happen the way that Blood remembers, Howse recalled. “It wasn’t like in the movies, where they just wake up,” he said. “There were a couple times during the coma where he showed signs. Then they would fade again. I remember the doctors telling him to move his hand, and he would move his hand. Or move his foot. It wasn’t like someone just wakes up, and they’re like, ‘Oh man, I have a story to tell you!'”

It wasn’t clear if he’d ever regain consciousness. At one point, the doctors gathered Blood’s close friends and family members in a conference room. “It was his mom, stepdad, brothers, sisters, a couple uncles, his girlfriend, and I — the place was standing-room only,” Howse said. “The doctors showed us some x-rays and CAT scans on an overhead. They said, ‘This is where the bullet is, this is where the fragments are sitting, and this is what to expect from this point: He could stay days or months like this. He might never wake up.”

“The doctors said he could experience brain damage, motor-skill loss, memory loss,” said Howse. “Because it was a brain thing they didn’t know — and that was all based on if he was gonna wake up at all.”

Blood gradually woke up over the next five or six days after spending twelve days in a full coma. But he wasn’t aware of everything going on around him; these were probably the times when he heard voices in the room, and felt like they were percolating into his dreams. He seemed bleary and would say the kind of garbled, incoherent things that people say when they’re coming out of a deep sleep. His blood pressure was still touch and go.

When he woke up for good, he remembers people and lights all around him. His head was wrapped in a huge bandage, and all his shaggy, tangly brown hair had been shorn off. A feeding tube dangled uselessly from its stand — apparently he had pulled it out of his nose several times.

The tattoo machine lay in a drawer beside his hospital bed.

Blood spent about three weeks in the ICU and two additional weeks in a regular hospital bed. His mother fed him ice chips. His friends still came to visit every day. Then on August 20 he transferred to Fairmont Rehab in San Leandro, which Howse describes as “something out of a David Lynch film.”

“There were a lot of people in various states of disrepair,” he recalled. “Honestly, no hospital is a very pleasant place to be. I have yet to go into a hospital where I say, ‘Oh yeah, I could see staying here for a while.'”

At that point, Blood’s brain was still swelling, and a large piece of his skull was still sitting in his gut, like a single pickle fermenting in a jar. The bullet remained encased in scar tissue, resting right against his brain stem. He had absolutely no muscle control in his right hand. He couldn’t walk, feed himself, or even hold a pen. He wore a hockey helmet to protect the hole in his skull. His future in the art business was uncertain.

“My little brother was a hyperactive child, so he had to go to special school with padded rooms and stuff,” said Blood. “He was picked up by these short yellow buses that were full of kids wearing helmets and in wheelchairs. I used to make fun of him all the time. Well, he came to the rehab and was like, ‘Remember when you used to make fun of me for having to ride the short yellow bus with the kids in the helmets and the wheelchairs? Now you’re wearing a helmet in a wheelchair. Ha ha!”

At some point during the Highland stint, Blood realized that his right hand was toast. “The whole right side of his body was pretty much numb,” his friend James said. “I did a tattoo on his leg, and he couldn’t hardly feel the tattoo getting done.”

“I think the medical term is ‘micro tremors,'” added Blood’s friend Tobias. “When he tries to focus and do something, it doesn’t do what he wants it to do because of the damage to his brain and spinal chord.”

So, hoping he could tattoo again one day, Blood began focusing on his left hand. His rehab nurse objected. She came in on Mondays and tried to get Blood to throw darts with his right hand. “Throw darts, put smaller box in a bigger box. Hand-eye coordination, dexterity shit,” said Blood. “I was already dealing with not being able to walk, having to be in this hospital bed, and wear this stupid hockey helmet. And this fuckin’ lady is telling me to do shit with my right hand,” he said. “It pissed me off.”

The medics at Fairmont were more open to the idea, but still didn’t understand what motor skills Blood needed for tattooing, said James. “His occupational therapist didn’t get the concept. Squeezing some Play-Doh is good for normal people, but Blood wanted to use his hand for a whole different thing.”

Tattooing requires two hands, one to stretch the skin tight, the other to handle the machine. Blood eventually trained his right hand to the point that it could perform simple functions, like holding flesh in place. But his left hand is the one with all the dexterity.

Over six months of living with his friend James in Petaluma, Blood went from using a walker and wearing a helmet to walking upright, riding a big tricycle around, having an in-depth conversation, and drawing and painting again — albeit left-handed. He learned to live in a world where most objects — from scissors to cabinets to refrigerators — are designed for right-handed people. He drew his first left-handed tattoo on his mother Linda in March of 2007: a Felix the Cat with the number 13 under it. Two years later, he plunked out his autobiography on a 1960s Olympia typewriter. He finished it in three months, starting in April, 2009 and typing the last word on July 12, the anniversary of the shooting. He had a friend tattoo the book’s title on his stomach, right over the scar where his skull had been: “Keep Laughing.”

Blood’s art career is starting to attain some momentum again. He’s now part of an exhibition at the Old Crow Tattoo Gallery, in which every artist gets a nine-by-three-foot wall space to use as a canvas. With twenty-two contributors, the show is pretty diffuse and a little outsider-ish — even for a tattoo gallery in Oakland. One wall features a collage of handmade decals, which advertise things like meat pie and fake vomit. Across from it sits a huge praying mantis, drawn in electric-blue spray paint. Another painting shows a sinister figure with a smeared face, and a warning sign painted across his stomach: “Back alley rapist on the prowl.”

In contrast, Blood’s paintings have a much earthier palette — all reds, browns, and grays. He did most of them on pieces of cardboard, drafting with an ink pen and filling the colors in acrylic. They show some of the images that float across his mind’s visual screen: bloody axes, anatomical hearts, a snake popping out of a flower to bite him in the face. He pointed to one that shows a heart with three wings, and a bloody eye. “The bleeding eye is the struggle, and the wings mean I’m still flying forward,” he said, matter-of-factly. “The third wing means I’m abnormal.”

There’s beauty in Blood’s work, but it’s always presented in the most grotesque and unsettling way possible. Some paintings show winged raptors, fanged serpents, and other carnivorous reptiles. One features a huge, clawed lobster. Mostly, though, Blood fixates on skulls. He draws skulls with things sprouting from their eye sockets, skulls with axes for cross bones, skulls with Swiss cheese holes and other deformities. One skull has heart ventricles coming out of its right side.

Blood calls that a self-portrait, of sorts. He pointed to a huge, jagged rift between the skull bones, right where his heart emerges. “That’s where I was shot,” he said.