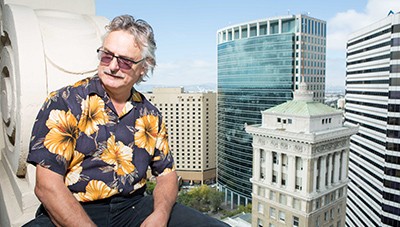

Central Services is located two stories above the top floor of Oakland’s Tribune Tower, according to the elevator directory. To procure services, take the elevator to its terminus at the twentieth floor, step through an unmarked door into a zone that hasn’t been renovated since the Tribune Tower housed Tribune writers, then climb two more stories to the twenty-second, where John Law sat on a recent afternoon, listening to Sonic Youth in his matchbox office.

Law, 56, is Central Services’ licensed inspector. He’s also a neon sign technician, responsible not least for the Tribune Tower’s beaming signage and clock arms. For decades, Law improved the messages on big, public advertisements without permission with a crew known as the Billboard Liberation Front. Overnight, they transformed Joe Camel from sax man to death merchant, for instance. Much of what Law does today is archival; he stewards historic fast-food fixtures such as the Doggie Diner Heads and the legacies of Bay Area countercultural entities the Suicide Club and the Cacophony Society. The latter implicates him in Burning Man, an event he cofounded, stopped attending in 1996, and doesn’t care much to talk about anymore.

“I don’t dislike Burning Man as an event. It’s a big party where you can get laid on drugs for the first time, which is great,” he said. “The politics behind the corporation that owns it are as byzantine and unpleasant as any giant corporation. It’s a machine with a really wonderful PR department.”

Still, Law likes to talk about Burning Man’s spiritual forefather, Gary Warne. In the Seventies in San Francisco, Warne started a free school called Communiversity. In 1977, Law arrived in the city and joined Warne’s newly and loosely formed Suicide Club, which provided a common banner for an array of pranks, theatric street performances, and urban excursions. In 1981, Law was issued a $10 citation for climbing on the Golden Gate Bridge. He eventually scaled the structure more than one hundred times.

Warne emphasized free. He thought equating value and dollar value was stupid. He also thought of urban infrastructure as a control mechanism to be subverted, but considered likeminded predecessors, such as the Situationists, to be pompous intellectuals. And crucially, Warne resisted the classification of Suicide Club events as works of art, Law explained.

“Gary helped create a subculture and inculcate it with these ideas that clearly had legs. He was a visionary, and the only reason you haven’t heard of him is because he died at 35,” Law said. “He’d do an event that turned people on and later it would become an industry. He wanted these things to be our lives, rather than just periodic endeavors. At the time I was just an eighteen-year-old who liked to climb things.”

After Warne’s death, Law cofounded the Cacophony Society in 1986 as an extension of the Suicide Club. From the group sprung Burning Man, SantaCon — which Law participated in until 1998, when he and a cabal of Santas climbed the Brooklyn Bridge, and today endures as more of a festive pub crawl for normies — and Chuck Palahniuk’s Fight Club, which was based, in part, on the author’s experiences in a Portland chapter. Billboard Liberation Front, which originated in a Suicide Club action, emerged as an independent entity with Law assuming the name Jack Napier to avoid legal trouble.

“Statute of limitations isn’t up on a lot of that stuff,” Law said. “But I’m not worried about it. We can make an excellent argument about how we actually improved their advertising campaigns by getting more publicity. I can bring in plenty of experts and they’ll tell you that any increase in name recognition increases unit sales. So I’d countersue for back-earnings. It’d be funny.”

Why did the BLF fold? “Well, when Banksy popped up, he was anonymous and everyone wanted to know who he is,” Law said. “We were anonymous for thirty or forty years and no one cared who we were anymore. So I figured it was time to retire.”

Did altering the Tribune sign ever cross his mind, even hypothetically? “No,” Law chuckled. “I don’t piss where I eat.”

Law started working on the Tribune Tower in the mid-Eighties, through the American Neon Sign Company based in Jingletown. “I was a young guy and so the old guys loved me because I’d go out on the wall and then hang my ass in the Bosun chair,” he said. “I’d just have a cigarette and check out the view.” Following the Loma Prieta Earthquake, however, the structure was red-tagged and slated for demolition. “It got trashed,” Law recalled. “The windows were left open and water destroyed the elevator shaft. I got sad about it. This is a singular building.”

In 1996, though, Law noticed that one of the sign faces was on. He’d been the last person to touch it. “By complete coincidence, I looked in and there was a bunch of suits in the destroyed lobby,” he said. “I told them I used to work on the neon and I got the card of the construction manager and bugged him for two months until I got the job.” Ever since, Law has spent about twenty hours a year dangling over the street below. Part of the deal involves the office space, he said. “Let’s just say it’s always been an equitable relationship for everyone.”

One side of Law’s office is full of books about music, street art, and the like. Much of the room is stuffed with archival material collected for Tales of San Francisco Cacophony Society, a book edited by Law, Kevin Evans, and Carrie Galbraith and published in 2013. The other side of the room is full of books about bridges, a longtime fixation of Law’s, both as surmountable structures and feats of engineering. On a lark, I asked about the new Bay Bridge.

“Oh,” Law perked up. “Do you have five hours?” Aesthetically, he’d award it seven out of ten points, with special props for the vistas created by the open deck design, but that doesn’t account for the footing problems, seepage in the concrete stanchions, rusting bolts, an out-of-plumb tower, and so on. The biggest issue, he said, is the self-anchoring, single cable design element. “I’m not an engineer, but engineers are saying this too,” Law noted. “It will come under untested stresses and we don’t know what will happen.”

Law went on about historic bridge collapses, the ones precipitated by circumstances and forces of nature so bizarre that it was impossible to even blame the designers. Then, Law gestured toward his phone. There he was, smiling in a floral shirt at the very top of the new Bay Bridge tower. “It’s still fun to be a sneaky old guy,” he said.

Thank you for this article. It’s always good, in a sad way, To see mention of Gary Warne. He was very encouraging at the very beginning of my harmonica teaching career in S.F.’s inner sunset during the mid-1970’s… Thus any good karma I have Gained through my work since then accrues partially to his account… He was a very interesting person and I wish those who knew him better than I (Here’s pointing at you, John Law) would write more about him Someday, before they join him in laughing at us from above!