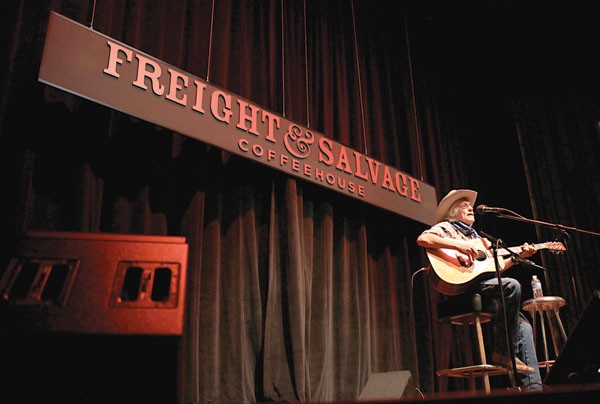

Steve Baker looked buoyant the day before the grand opening of Freight & Salvage Coffeehouse, at its new, well-lit, swanky Addison Street venue. A lithe, wiry man with a tattersall shirt and chunky glasses, Baker has served as the Freight’s executive director for twelve years, but he’s worked there on and off since 1983, when he was fresh out of law school. He helped turn the Freight & Salvage into a non-profit entity at a time when its operators were worried about keeping the doors open. Sixteen years later, he helped quarterback the move into a former garage and auto shop smack in the middle of downtown Berkeley’s newly designated arts district. The move took ten years, $11.7 million, and a lot of shrewd decision-making. Yet if all goes as planned, it will not only help cement the Freight’s place in Berkeley’s cultural history, but give the coffeehouse a pivotal role in the city’s gradually evolving downtown.

The auditorium in Freight & Salvage’s new building seats twice as many people as the old performance hall (440 as opposed to 220), but it also has enough room for another 180 standing. It’s a green building, with a living roof, a bamboo stage and floor, and recycled Levi’s jeans in the walls for insulation. The new chairs from Swerve Design give the Freight a more contemporary edge. On slow nights, they can be replaced by modular tables to make the place look more like a nightclub. The new Meyer Sound system makes performances audible throughout the lobby and at the front entrance. Upstairs on the mezzanine level are five empty practice rooms, where performers will offer workshops and master classes of the sort you’d find in other performing-arts-oriented nonprofits.

It’s been a tortuous journey from conception to actualization: Baker describes it as a “design first, build later” type of process. Some time in the late 1990s, he got a call from Berkeley’s economic development manager, Michael Caplan, who at the time was helping conceptualize the arts district. In the early 1990s, Berkeley had funded a study to determine why people were coming downtown. “It was the arts,” said Caplan, “including Berkeley Rep, the movie theaters, university-oriented cultural events, and food — there were over eighty restaurants in the area. Those were the main reasons people were coming here.” City boosters decided that an “arts district” would be the perfect thing to anchor their revitalization efforts, and they designated Addison Avenue as its locus: That street is now home to Berkeley Repertory Theatre, the Jazzschool, the Aurora Theatre, and the Addison Street Windows Gallery, in addition to the new Freight & Salvage. It will soon border a new 1,400-seat club leased to the owners of Slim’s and Great American Music Hall (where once lay the UC Theater), and a second iteration of UC Berkeley’s Pacific Film Archive theater, which plans to relocate to upper Center Street downtown. “You could break it down into seats,” said Caplan: Berkeley Rep’s Thrust Stage is about 400, the Roda is about 600, Aurora has 200 seats, and the UC Theater will be 1,400. This will help restaurants in the area.”

Caplan was in conversations with various arts organizations around the time he began courting Baker, but the Freight stood out as an especially desirable tenant. “Traditional music — bluegrass, Cajun folk, singer-songwriters — it’s something people associate a lot with Berkeley,” said Caplan. “We’re really building on what we think are Berkeley strengths.”

Fortunately, the guy who owned the auto shop was also a big music buff and supportive of the Addison Street artsification. People used to joke that he was an arts institution in his own right, since he always had quality jazz music playing in the garage, Caplan said. He sold the property to the Freight in 2000. (The city granted the Freight a $527,000 loan for the acquisition.) Freight & Salvage also got the deed to both the auto shop and the building next door, which at that time housed the Capoeira Arts Café. Once he secured the deal, Baker enlisted the help of architects Donn Logan and Marcy Wong to completely redo the building’s interior. They kept the original façade — it still says “Stadium Garage” in large block lettering — but changed everything else. “We chopped the building off at that line,” said Logan, pointing just beyond the front wall to a place where the original two roofs intersect.

The tricky part was raising money. For years they continued renting space to the cafe and the Berkeley Rep, which used part of the dormant auto shop for costume storage. They spent the next nine years soliciting donors, some of whose names are inscribed in a placard at the entrance to the new performance hall. (The Freight’s opening week program contains the list of donors in its entirety.) But a lot of that credit also goes to Baker, who figured out how to build the organization’s capacity and transform it from a funky music space into a cultural institution. Baker abandoned his law practice upon taking his post at the Freight, and has since devoted his life to the preservation of American folk music. It seemed apropos. After all, he keeps a guitar in his office, and as a lawyer he often represented artists and performers. “On Steve’s part it took a true vision,” said Caplan. “It was a change of size, so the scale was much riskier — or it seemed so at the time. … We’re so glad they were willing to take that risk.”

Running a big venue does seem to put the Freight in a more perilous position, but Baker seemed sanguine on Wednesday — probably because the venue expected to sell out all four of its opening week shows (it did as of Friday). Ticket costs remain in the $18 to $26 range, a price originally set to keep shows in the old coffeehouse from selling out. Overhead costs have increased, but Freight marketing director Lisa Manning says that if sales remain high, ticket prices will ultimately go down. Caplan think it’s a win-win: the Freight has a built-in crowd that now has reason to dine in the area, and the downtown location will make them accessible to a broader mix of people.

And he’s probably right. The club’s opening night fiddle summit played for a packed house, with at least thirty people standing in the aisles. Next door, Addison Street Windows Gallery featured a Freight-centric art exhibit with prints and oil paintings of 1930s- and ’40s-era musicians, plus posters of icons like Odetta, Ricky Skaggs, Ramblin’ Jack Elliott, Vienna Teng, Cascada de Flores, and the Tin Hat Trio. Parking was scarce for blocks at 9 p.m. on a Thursday, making the area seem less like downtown Berkeley and more like the SOMA district of San Francisco. For the 41-year-old coffeehouse, it seemed like an auspicious beginning.